Author: Alan MacKenzie

“It’s important to be humble and understand that there are always great challenges ahead of you”, Björn Hugosson, Stockholm’s chief climate officer, says.

Since 1990, the city has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by two-thirds, alongside a growing population and economy. But even with more than 30 years of climate action behind them, the city is still being challenged – and challenging itself – to do better.

Following the award of one of the first ten ‘Mission Labels’ from the EU, which recognises the strength of the city’s plans to reach climate neutrality by the end of the decade, Hugosson has some helpful insights for cities beginning that same journey.

“You need a lot of partners – the city alone cannot address all the issues”, he says. “One thing is to look at the partners that you already have. Perhaps there is a university in the city that you have some work with, or there is a supplier or an energy company or something. Start with the cooperation that you already have and bring in the climate mitigation issue in the discussion and talk. What could you do together? How can we take advantage of this Cities Mission and the funding possibilities that you have and try to build and enhance this cooperation?”

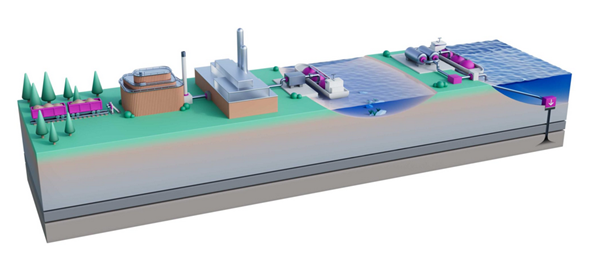

The current plant – Europe’s largest biomass-based combined-heat and power plant – and the planned CO2 shipment and storage.

One important cooperation in Stockholm is on a ‘bio energy with carbon capture and storage’ (BECCS) plant, connected to an existing heat and power plant, to begin operating in 2025/26. Backed by EU funding, the BECCS plant has the potential, says the city, to “remove around 800 000 tons of CO2 annually” and demonstrate its viability for others to follow.

“Critical stakeholders” on the project include funders and investors, private companies in and outside the city, as well as the city’s municipal companies and the district energy provider, Stockholm Exergi, which is 50% owned by the municipality.

Different scale, same ambition

Seven-hundred kilometres away, a smaller east coast city in the Nordics has also welcomed the award of a Mission Label.

Like Stockholm, the city of Sønderborg in Denmark has a longstanding ambition to reduce its emissions and wants to make an outsized contribution to decarbonisation through its interaction with the rest of the 100-plus Mission Cities in Europe and beyond.

“If we look at Sønderborg itself, our goal of climate neutrality, we make a small impact ourselves on the global footprint”, says Allan Pilgaard-Jensen, head of Sønderborg’s Project Zero ‘masterplan’. “But we make a much bigger impact by sharing our ideas and plans with others throughout Europe. So that has been our philosophy and goal and I think it fits very well with the EU [Cities] Mission”.

Critically, Sønderborg’s ambition is shared by its stakeholders, who they try hard to bring aboard.

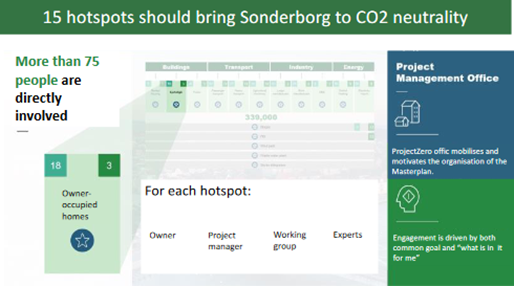

“I’m actually very delighted about how all our stakeholders are working closely together to achieve our goals”, Pilgaard-Jensen says. “We have more than 75 people that are organised in groups – we call them ‘hotspots’ – that take the responsibility of decarbonising their specific areas”.

So for the city’s buildings sector, stakeholders like housing associations, homeowner representatives, craftsmen, utilities, energy consultants, landlords and municipal authorities work together in dedicated hotspots for rented homes, owner occupied homes, and public buildings.

Going one step further to encourage integration across different sectors and avoiding ‘silos’ – a common roadblock to success in public and private organisations – all hotspot managers meet quarterly to provide updates and discuss risks and solutions.

“We think that it is essential to work across silos in our plan, to make the decarbonisation as energy efficient as possible. So that is actually what I’m most proud of”.

Mission focused

Solving deep problems, like organisational silos (and others that might be well known but thus far unsolved), is a key part of the ambition of the 112 cities involved in the EU Cities Mission, and the Cities Mission Platform, NetZeroCities, which helps them with their climate goals.

Through a tool like a Climate City Contract (or CCC, which every ‘Mission City’ is set to develop as a participant in the EU Cities Mission), cities are forced to reconsider longstanding systems that weren’t designed for the cross-cutting work needed to deliver on their climate ambitions.

In Sweden, a similar CCC model has existed for a number of years through the national ‘Viable Cities’ innovation programme.

“That has had a positive consequence that we are challenged to work in new ways”, says Björn Hugosson. “When you work a long time with a subject like climate mitigation, you sometimes get stuck on the same path, in the same way of thinking. So the CCC process has enabled us to try out new ways to think, to produce new instruments to work with”.

One of these in particular is the city’s Climate Investment Plan.

“This enabled us or forced us to work together with the finance department of the city. And this has proven very useful and very fruitful to bring the climate strategists and financial strategists together around the same table, working around the costs, the investment costs, operational costs, and try to do the calculations as thoroughly as possible”.

Notably, for a city with years of experience in climate action, there were new perspectives to discover through the CCC process, Hugosson says.

“This has given us quite a new view on what is actually in front of us when it comes to the magnitude of investments. Not least in the private sector. So we see what kind of businesses that we need to bring into the alliance and to work together with”.

Willing and labelled

And as cities who have successfully submitted their CCCs, had them endorsed, and then received the Mission Label, how did it feel to be among the first ten awarded?

“It felt great to have this acknowledgment that our plan is considered as a solid and trustworthy plan for 2030. It created quite some attention, both in the city organisation, on a political level, but also with our partners, with the businesses and academia that we are working together with”, says Hugosson.

“So, there is a general understanding that the Cities Mission from the EU is something important [and] addresses the very high ambition of the European Union to really do something about climate change and to create some kind of spearhead of cities addressing this issue”.

The recognition that cities have developed a solid plan for rapid decarbonisation, signified by the award of the Mission Label, is a vital element for Mission Cities. Attracting financial partners will be a going concern for all, including Sønderborg.

“We also expect it will improve our opportunities for funding”, says Pilgaard-Jensen, who was “delighted” by the award and the increased attention for the city’s climate plans.

“Our plans for funding are necessary to realise our mission and involve big investments from both public and private stakeholders”, he says. “And that is definitely what we would like to achieve”.