Author: Katherine Peinhardt

A mission is meant to be transformative. In fact, the Cities Mission, alongside the other EU Missions, was modelled after humankind’s journey to the Moon. Much like the immense societal, technological, and scientific transformation that came about as a result of the mission to the Moon, the EU’s journey to climate neutrality means a radical change. The Cities Mission to forge 100 climate-neutral and smart cities by 2030 requires that we address the climate crisis by changing the whole system.

The climate crisis is uniquely complex, bridging the realms of technological, economic, financial, institutional, and social systems. That means that our approach must dig deep, examining the structures and barriers to change that have held us back from collective action at scale. Prof. Mariana Mazzucato, who was part of the process of creating the EU Missions, has pointed out that big-picture problems like the climate crisis can be a chance for systemic innovation: “Mission-oriented innovation policy has a major part to play in delivering better quality growth while addressing grand challenges, but the changes in mind-set, theoretical frameworks, institutional capacities and policies required are by no means trivial.” This transformation starts with collective willingness and openness to changing our systems, institutions, and infrastructure to rise to the task of climate neutrality.

To get to systems thinking means that we will have to break free from our current norms for taking action – norms that leave our efforts fragmented and unable to build off one another. In many cities, the status quo for climate action has been to create top-down policies supported by a disconnected group of projects, initiatives, and platforms. This neglects how real change happens: by connecting people, ideas, and actions. We have an opportunity to reframe our climate future by reframing the ways we identify, plan, and implement change. And with any luck, this will go beyond climate neutrality to create more equitable, inclusive, and healthy places to live in the long run.

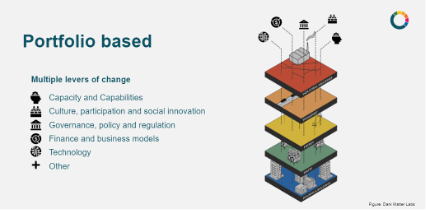

What comes first is understanding the system; drawing connections between the complex and overlapping sectors, processes, and players that impact our collective ability to take climate action. Getting the context right, especially at the local level, ensures that we see important patterns, whether that means recurring structural barriers to action, or opportunities to amplify change across sectors. It is these types of patterns that help us to more effectively pinpoint opportunities for change and follow through on them for maximum impact. Often, these opportunities can be seen through the lens of different levers of change: Governance, policy and regulation; technology; finance and business models; democracy, social innovation and social change; and capacity and capabilities. Getting a good grasp of the local landscape, including the status of these different levers, helps us to know what kinds of change are possible.

Once we understand where the opportunities for climate action lie, we can begin creating a portfolio of actions. Ideally, this portfolio is diverse, touching on multiple levers of change to create a well-rounded and iterative plan for action. Leading with a portfolio in which different types of action are integrated offers the chance to learn, adapt, and gather insights to amplify impact. In Valencia, Spain, the Missions Valencia now take a whole-picture, EU Missions-style approach to four connected goals: creating a “healthy, sustainable, shared and entrepreneurial city.” This has led Valencia to kick off a “constellation of innovation projects with an impact on the missions coming from the whole innovative ecosystem.” In this way, Valencia has created a platform for projects and initiatives to build on one another and create lasting, cross-sector change.

Collaboration in making the portfolio of actions a reality is the natural next step. At the city scale, structures like a Transition Team can bring people from different sectors, areas of expertise, and backgrounds into coalition. This can take shape in many ways: In places like Leuven, Belgium, a new municipal authority group has been formed to create ongoing opportunities for locals to have their say. The City of Leuven acted as a founding member of Leuven2030, a nonprofit which now gathers more than 600 stakeholders working toward a “city with fewer emissions and a better future.” The group’s broad scope of engagement is reflected by the fact that memberships are received in six different categories: citizens, civil society organisations, businesses, knowledge institutions, authorities and semi-public authorities. The group composes broad-sweeping roadmaps for the City and its climate actions, working alongside urban planning experts to create plans like the Roadmap 2025 · 2035 · 2050, which lays out eight areas of priority action and 80 so-called “project clusters” agreed upon by stakeholder members.

Among the most important ways we can foster this type of meaningful collaboration is open governance. Transparent and participatory approaches to governance mean that community members’ priorities are considered, or even better, that they guide policymaking from the start. Investing resources into creating infrastructure and systems that gather ideas from the community can change not only the chances of success for climate action, but also the ways that our communities collectively make decisions in all areas.

We know that a lot must change for cities to become climate neutral. Systemic innovation is a lens through which we can make that change possible – with an understanding of local barriers and opportunities, a comprehensive portfolio of actions, and a strong ecosystem of collaboration, the mission’s objective is in sight.

Citations

Mariana Mazzucato, Mission-oriented innovation policies: challenges and opportunities, Industrial and Corporate Change, Volume 27, Issue 5, October 2018, Pages 803–815, https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty034