Author: Alan MacKenzie

The EU Cities Mission aims to make over 100 cities both climate-neutral and smart by 2030 – but what is a “smart city” and how does it help its climate goals?

On Sweden’s southwest coast, the city of Helsingborg sees itself “as an enabler of innovation, rather than the innovators ourselves,” says Åsa Bjering, the programme manager for the city’s department of ‘Innovation and Green Transformation’.

The distinction is important.

A 2020 European Capital of Innovation Awards finalist, Helsingborg is well known for its forward thinking, and Bjering’s department brings together both climate activities and smart innovation where they can act in unison.

“It is important that people working on smart city policies understand that climate neutrality is their goal”, Bjering told attendees at a panel at the Smart City Expo World Congress in Barcelona in November – though people working on climate-related activities should also understand how technology can help them.

Irma Ventayol i Ceferino, from Barcelona City Council’s Climate Change and Sustainability Office, also a speaker on the panel, shared a similar sentiment.

“To be a smart city is not a goal or purpose in itself. Smart and climate policies should be the same [and] these policies should respect planetary boundaries and meet established socio-environmental standards”, says Ventayol i Ceferino.

Innovation, therefore, is not a city’s primary function. But if it improves the city for its inhabitants and assists its climate goals, it should be welcomed and facilitated.

But how are smart cities connected to the goal of climate neutrality? And what makes “smart” cities smart?

Greater efficiency is the first part of the answer. Using resources more effectively, through better technologies or automation, allows the scarce assets of a city to go further and to where they need to be.

However, smart cities go “beyond the use of digital technologies for better resource use and less emissions”, says the European Commission, meaning “smarter urban transport networks, upgraded water supply and waste disposal facilities and more efficient ways to light and heat buildings. It also means a more interactive and responsive city administration, safer public spaces and meeting the needs of an ageing population”.

Efficiency alone, therefore, isn’t a new answer to city problems in general and won’t be the answer to those above.

What is required then are two connected elements. The first, and most innovative, is data.

“As our urban spaces are increasingly enabled by sensing and automation technologies, data is becoming central to how we understand and design our cities”, says Jane McLaughlin, a city advisor on the NetZeroCities project who moderated the panel in Barcelona.

“Working together to design approaches to how we capture and use data in the city is key to help us to create climate-neutral, smart and, crucially, human-centred cities, designed for and by people. We’re already seeing great innovation in this area from cities all across Europe, with an inclusive and collaborative approach vital to ensure everyone in the city is onboard and involved in the transformation”.

From traffic and temperature levels, to air, water, and soil quality, monitoring and measuring changes as they happen can reveal insights city managers have never had before.

Decision making, in theory, not only improves, but so does its timeliness, and events can be forecasted and planned for or even prevented.

Buying-in, or checking-out?

Data collection also presents opportunities for cities when it comes to garnering the support of citizens for their climate activities.

Transparent collection and availability of data can make it clear for citizens how local decisions have an impact – and allow cities to make plain their value and successes.

In Helsingborg, sensors measure air quality, and the results are reflected on a dashboard in classrooms, sparking discussion between pupils and teachers, spreading out into their homes and community. Citizens, young and old, can easily ask themselves, “What do I contribute?”

Even better, the sensors used were already in place: an excellent example of the difference between technology for its own sake – as warned against by some panellists at the congress – and “smart”.

The city is already partnering with companies to replicate its success.

Trikala, Greece, has had similar results communicating to citizens both on smart and climate-neutral action. Using sensors to switch streetlights on and off based on natural light has made energy savings of 30%, saving money for the municipality, and showing how climate and smart policies can align.

But with any intervention, there are inevitable risks as problems are solved and replaced with new ones.

“Massive use of sensors without creating collective intelligence makes no sense. The data must help diagnose the problem, generate knowledge, make it visible and understandable, generate debate and awareness and must finally be useful to facilitate the necessary change and to help facilitating decision-making”, says Irma Ventayol i Ceferino.

Again, innovation and data and technology is not an end goal. There can be data overload and too much to process.

“Much greater collaboration is key to turning climate and urban data into usable knowledge that positively impacts society”, says Sam Pickard, a researcher at the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre, who are working with local decision makers in Barcelona to co-produce climate services as part of the Impetus4Change project.

This collaboration of both researchers and decision makers is critical to sort through the “mountain of data” produced by cities and produce the correct tools for citizens, though Pickard notes that access to data isn’t always easy for researchers who would like to support cities in their climate neutrality journey.

Changing reality with virtual cities

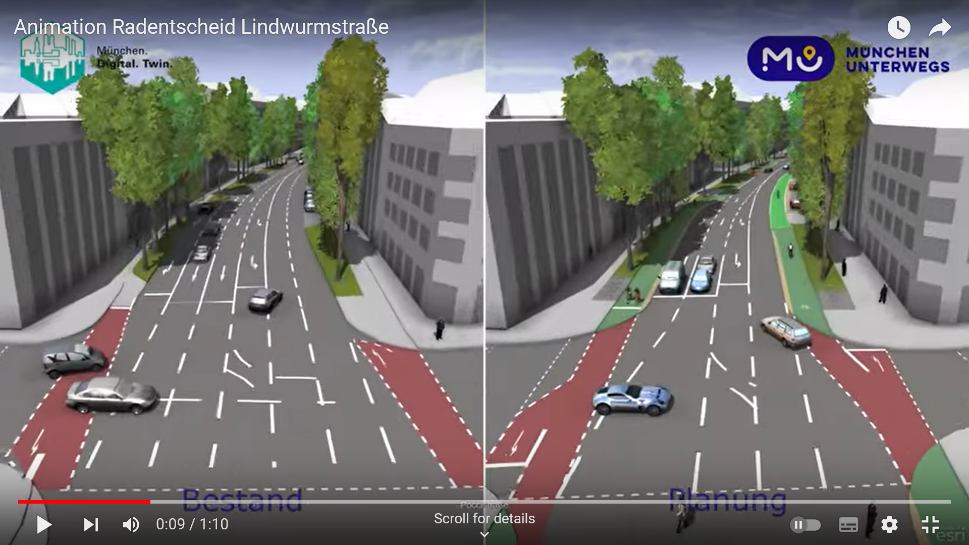

One of the most powerful tools of the smart city is the ‘digital twin’ – a virtual copy that renders the city’s infrastructure in 3D, even down to individual trees, where proposed interventions can be tested or visually modelled to display proposed changes before real-world interventions take place.

One example given at the smart cities panel in Barcelona concerned installing a new solar panel. A proposed installation can first be simulated in the digital twin, showing how much electricity will be produced and what effect the location will have considering the surrounding trees and buildings.

A similar capability is possible in Klagenfurt, which launched its twin in April 2023. Composed of 19,000 images, the virtual city can reveal the potential for solar energy on individual rooftops and determine an optimal number of solar panels to install.

Photo: München Unterwegs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWWWsmqBSD0

Along with the twin, Urban Data Platforms, as used by Munich, act as “the central data hub of the Digital Twin”, according to the city’s project website, where it “is used to network formerly separate stand-alone solutions into a common ecosystem for the city”.

In other words, a data platform is a one-stop-shop for various data streams from across the city’s departments, informing city staff and researchers, including in real-time, as well as the public and business.

Digital diligence

Protecting a smart city’s critical infrastructure is now a priority on a par with protecting its most important physical assets. And the personal data of citizens also needs serious defense, not only for their privacy and safety, important as that is.

The support of city administrations and the legitimacy of their technological interventions – which can appear opaque and unaccountable when fronted by a piece of software or offered on an app – will depend on it.

The same idea was supported by the panellists at the congress in Barcelona.

Proactive communication to citizens about the use of data creates a level of transparency and trust, says Konstantina Zachari, advisor to the mayor in Trikala. While in Helsingborg, there have been sessions with politicians and citizens to discuss data use.

This is then the second part of our answer to what characterizes the smart city, and what are its strengths and opportunities: citizen participation and an “interactive and responsive city administration” (as the European Commission defined it earlier).

Data and ethics is addressed by the local government in Barcelona with guarantees on the use of personal data and privacy.

Decidim BCN, a digital platform for citizen participation in the city, works in an open-source way, and information is public and transparent, says Irma Ventayol i Ceferino.

Knowing who owns the data is critical.

Cities, whose duty is to work for the public good, apply very high data protection standards, says Wibke Borngesser, a project manager at the City of Munich – which is sometimes also a constraint for developing policies when, in certain cases, only aggregated data can be used.

Street smart

Beyond the many possibilities of smarter cities and their relation to climate action, all citizens – not only those who are familiar with apps or the online world – are the responsibility of city managers.

“Even though digital tools are very helpful tools to get a profound basis for discussions with all kinds of stakeholders, they might not always be the best choice”, says Wibke Borngesser.

“One has to make an effort to explain what the tools are, how they work, and what data they use. And we also need to leave choices – digital alone might not always be the answer”.

In one project, there is a very diverse district in terms of languages, income, and age: “If we only offered digital approaches, we wouldn’t be able to get in touch with all the citizens. We need to be there in person as well to point out the other ways of participation and talk to people”, she says.

This view is shared by her contemporary in Barcelona, who warns of a “digital divide” and leaving people behind.

“Especially the people most vulnerable to climate change, such as the elderly or people with less education, may have difficulty accessing [Decidim BCN] … For this reason, it is important to continue participating in person”, says Irma Ventayol i Ceferino.

“Building inclusive cities requires we include new citizen voices and their knowledge in our deliberations over the future we want. But to include those at risk of being left behind requires tailoring our engagement efforts; this is why as part of the AGORA project we’re working to draw together and share experience of what works, in which situations, and with whom in terms of citizen engagement”, says Sam Pickard.

To face the future, cities will act smarter. To face it fairly, their digital revolutions will need to bring everyone along.

Innovation can help do so, but the contributions from panellists seem clear that tech won’t solve all the problems of citizen engagement, as it won’t solve the problems of decarbonisation, if the aim is innovation alone.

Put to use instead to serve citizens and support the city’s climate goals will truly be smart.