Author: Barbara Jarkiewicz

In cities, every tram line, courtyard and renovated apartment block is ultimately about the daily lives of residents, not about abstract climate targets. As Europe races towards 2030 climate neutrality goals, and cities are growing exponentially, one lesson from the Pilot Cities Programme is becoming clear. The cities that move fastest tend to be those that treat citizens as partners in the transition, rather than relying only on big budgets or smart technology.

Across the first cohort of 52 Pilot Cities, more than 184,000 people took part in activities that ranged from citizen assemblies and neighbourhood workshops to digital apps and citizen hackathons.

These efforts go far beyond simple add-ons to “real” climate policy. In many cases they are what made policy workable. Whether the issue was deep renovation, sustainable mobility or urban cooling, cities repeatedly discovered that technical solutions only took them so far. The real leap happened when residents felt that the transition belonged to them, that it reflected their needs and that they had a say in how it unfolded.

The examples emerging from the Pilot Cities Programme show what this shift looks like on the ground. They also hint at a different way of thinking about climate policy in Europe.

German cities build a “House of Change” for everyday climate action

In Mannheim, Aachen and Münster, the CoLAB project set out to answer a deceptively simple question. How do you move thousands of people from awareness to daily climate action?

Their answer started with a new kind of civic space instead of a single-point project. The “House of Change” is both a physical and digital platform where city administrations, citizens, community groups and businesses work side by side. Cultural venues host citizen summits and climate events. Innovation hubs run hackathons and workshops that invite residents to co-design solutions. The goal is to make climate work visible and social, something people can walk into rather than only read about.

Alongside these spaces, the cities co-created digital tools that help residents turn concern into choices. They guide users through “seven doors from knowledge to action”. People can see what lifestyle changes matter most, link their commitments to the city’s Climate City Contract and track their impact through national tools such as the Federal Environment Agency’s CO₂ calculator.

The lesson is straightforward. Maps of stakeholders are not enough. People need concrete invitations, intuitive tools and spaces where climate action feels achievable, shared rather than imposed. When that happens, engagement turns into a habit.

Turku shows how ambassadors and nudges can reshape everyday choices

Further north, the city of Turku took a different route to the same objective. Its “1.5 Degree City” project treated behaviour change as a collective project that involved citizens, local businesses and the wider city group.

Turku created a climate ambassador network, recruited from residents who were willing to champion low carbon lifestyles in their own communities. These ambassadors took part in dialogues, shared practical examples of sustainable living, and helped connect climate messages to everyday concerns like health, cost of living and convenience.

The city complemented this work with a free time mobility pilot project that used gentle nudges to influence how people moved around. Campaigns invited residents to test low carbon travel options and compare experiences. Behind the scenes, an online platform provided a shared data baseline for emissions and tracked both the “footprint” and “handprint” of local actors, helping businesses and citizens see the positive impact of their choices.

Turku’s experience suggests that behaviour change accelerates when people can connect climate action to tangible co-benefits. Healthier bodies, quieter streets, lower bills. Data helps, but so does trust. Ambassadors and dialogues can bridge that gap in ways that top-down campaigns rarely manage.

Liberec turns an energy community into a civic project

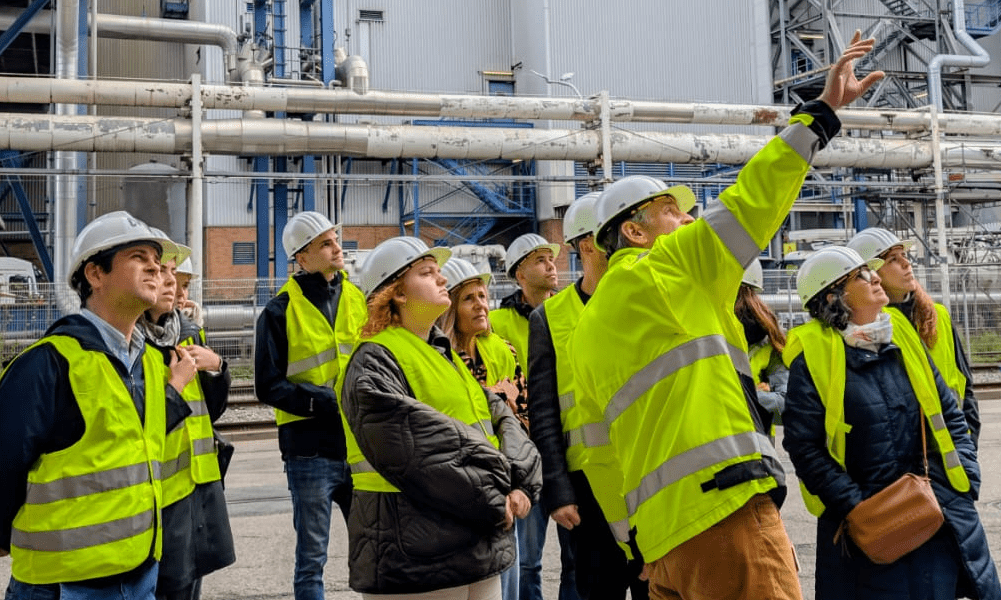

In the Czech city of Liberec, the pilot activity focused on setting up a sustainable energy community and preparing the ground for a broader energy transition. On paper, this might sound like a highly technical exercise. In practice, it became a lesson in how community building and climate policy fit together.

To create the energy community, the city brought together residents, the local heating plant, the technical university and private companies. Workshops, roundtables and public events served as meeting points where people could ask questions, share concerns and understand what the transition meant for their own buildings and bills. The project directly engaged 174 citizens through focused events and reached an estimated 20,000 more through a public campaign.

Inside the municipality, the pilot activity helped shift mindsets and a new City Transition Team emerged. Staff who had previously focused on purely technical issues began to see participation and social factors as essential parts of their work.

Liberec’s experience highlights a simple point. Energy communities depend on more than legal structures and infrastructure. They also rely on a social contract, and when residents understand how they fit into that contract, the path to deeper change opens.

In Limassol, cooling the city starts with listening

On the Mediterranean coast, the city of Limassol faced a different challenge. Rising temperatures and extreme heat were already shaping daily life, especially for people living in older buildings that were never designed for today’s climate. The LC³ project approached this problem through a new governance model called the Lemesos Commons.

In Limassol, cooling the city starts with listening

On the Mediterranean coast, the city of Limassol faced a different challenge. Rising temperatures and extreme heat were already shaping daily life, especially for people living in older buildings that were never designed for today’s climate. The LC³ project approached this problem through a new governance model called the Lemesos Commons.

Residents, landlords, city staff and other stakeholders took part in co-design workshops to rethink how existing buildings and public spaces could be adapted. Rather than starting with a catalogue of technical fixes, the city hosted conversations about comfort, cultural habits and shared responsibilities. Participatory budgeting exercises allowed residents to help prioritise interventions. The pilot project directly engaged 468 citizens through events that treated them as partners in decision making.

Limassol’s experience shows that climate adaptation is about changing how people think about comfort, space and what is possible in existing buildings. That kind of cultural shift only happens through sustained engagement and shared decision-making.

Seven Spanish cities build renovation strategies with residents

In Spain, seven cities joined forces in the URBANEW project. Vitoria Gasteiz, Valladolid, Valencia, Seville, Madrid, Barcelona and Zaragoza worked together to accelerate building renovation and urban regeneration. Citizen participation was woven into this effort from the outset.

Training programmes and workshops brought together construction professionals and citizen representatives. Local “Mission Agents” emerged as connectors between institutions and neighbourhoods, helping residents understand renovation options and voice their needs. More than 500 training materials were developed and over 800 hours of training delivered, building a shared language around what deep renovation really means and how it can be made fair.

A dedicated communication group and follow up project strengthened visibility and helped residents see their city as part of a wider national movement on building decarbonisation. Renovation stopped being only a technical requirement and became a collective project aimed at energy equity and better living conditions.

Guimarães and Cluj Napoca show what happens when engagement reaches scale

Some of the most visible results in the Pilot Cities Programme came from cities that placed citizen engagement at the very centre of their pilots.

In Guimarães, more than 12,000 residents took part in assemblies, mapping exercises, green belt activities and school projects. A Climate Pact turned from a mobilisation campaign into a governance tool and over 130 organisations signed on.

Cluj Napoca followed a similar logic in high density neighbourhoods. The city engaged thousands of residents through caravans, innovation camps, youth participatory budgeting and a Civic Imagination and Innovation Centre. Children were invited to become “Net Zero Champions”, sparking conversations about energy and renovation at home.

These examples show scale. When tens of thousands of people encounter climate neutrality not as a distant policy but as a local conversation, a school project, a neighbourhood event or a digital tool, the transition stops feeling like something that happens elsewhere. It becomes part of daily life.

© Guimarães / Laboratorio de Paisagem

What this means for Europe’s climate transition

Taken together, these stories point to a new baseline for climate policy in European cities. Citizen engagement no longer sits in the “nice to have” column. It is one of the main conditions for success.

The Pilot Cities Programme shows that effective engagement can take many forms. It might be an ambassador network in Turku, a House of Change in Mannheim, a Commons in Limassol, a Warm Home Hub in Galway or a climate pact district in Guimarães. The details differ from place to place, but in each case, people are able to see themselves in the transition and influence its direction.

For city officials, this means budgeting for participation with the same seriousness as they budget for new infrastructure. For national governments and EU institutions, it means recognising citizen engagement as a form of climate investment and creating funding frameworks that reward it.

Cities are where climate neutrality becomes real. They only function because millions of people get up every morning and decide to stay, work, raise families and build communities there. They are already showing that when given the chance, they will help design, test and carry the change. The task now is to make that the rule rather than the exception.