Author: Barabara Jarkiewicz

Bratislava is redefining how cities and businesses can work together to tackle climate change. Through the Bratislava Mayor’s Climate Challenge, the Slovak capital is showing that real progress on emissions requires shared responsibility, trust and transparency.

“The city has a direct influence on only about 11% of emissions in Bratislava,” says Marián Zachar, project manager of the Bratislava Mayor’s Climate Challenge. “Companies, residents and private transport are responsible for about a third of the rest. The city wants to lead by example through its own investments and policies, but at the same time it needs to motivate others to change.”

The initiative stems from the city’s Climate City Contract, which commits Bratislava to accelerate transition to climate neutrality committing to a 63% reduction of emissions per capita by 2030. The challenge gives that ambition a practical shape and invites companies to take measurable steps, such as improving the energy efficiency of buildings, installing renewable sources or introducing sustainable practices that support the city’s long-term resilience.

Ten companies (IKEA, Lidl, Billa, Kaufland, 365 Invest, HBReavis, Metro, Tesco, Corwin and IAD Investments Management) joined the first year of the programme, together covering twelve buildings with a combined area of almost a quarter of a million square metres. Their commitments are expected to save more than 3 GWh of energy in the first year. They also plan to install more than 3,000 kilowatts of photovoltaic capacity, about 15 percent of the city’s 2030 renewables’ target for the tertiary sector.

From City Hall to the boardroom

Bratislava’s approach is rooted in long-term cooperation rather than short-term benefits. “We don’t have direct financial incentives to offer, but what we can provide is an honest partnership on something that makes sense. We want to build cooperation based on trust and transparency,” says Zachar.

The city began by reaching out to retailers and asset managers, whose buildings contribute significantly to emissions and who are already active in sustainability.

“We decided to start with those who could make the biggest impact and who already understood the value of sustainability. We knew that if we could motivate competitors to work together, it would send a strong signal that this was about more than business. It is about shared responsibility,” Zachar explained

Each participating company sets two clear goals in the fields of energy and sustainability. Before joining, they consult with the city to ensure that their actions are achievable and aligned with the wider climate plan. “We really focus on energy efficiency,” says Zachar. “It is not always the most popular topic in sustainability, but it is the most impactful, and it also makes economic sense.”

Why cities need the private sector

Urban transformation requires enormous investment, that is far beyond the reach of public budgets, but collaboration with the private sector mobilises the capital, expertise and innovation needed to close this gap.

Businesses bring technical know-how, resources and agility that public administrations often lack. They can pilot new technologies, develop scalable energy solutions and turn climate challenges into opportunities for green growth. When companies invest in energy-efficient buildings, renewable infrastructure or sustainable mobility, they do more than reduce emissions. They strengthen local economies, create jobs and build public trust in the climate transition.

Partnerships like Bratislava’s also affect governance. By involving businesses directly in city-led climate strategies, they can increase transparency, accountability and public confidence that change is not just an administrative effort but a shared civic mission.

Yet such collaboration is not without its hurdles. Many cities face limited access to financing, complex regulations and varying levels of corporate readiness. Programmes like the Bratislava Mayor’s Climate Challenge are pivotal vehicles for change, as they provide a framework for cooperation, dialogue and action, enabling both parties to progress together.

Partnership in practice

The Challenge is also redefining how the city supports businesses in reaching their climate goals. When one company wanted to install heat pumps but had no space for drilling wells, the city made it possible.

“They found a small green strip of land owned by the city. Normally, a request like that might take long time to answer. But we created a process to make it possible. Now they can move forward with the installation and they are already installing it,” Zachar recalled.

That willingness to adapt has become part of the programme’s DNA. “We want companies to know that if they need to call the city, someone will pick up the phone. That is what partnership means,” Zachar says.

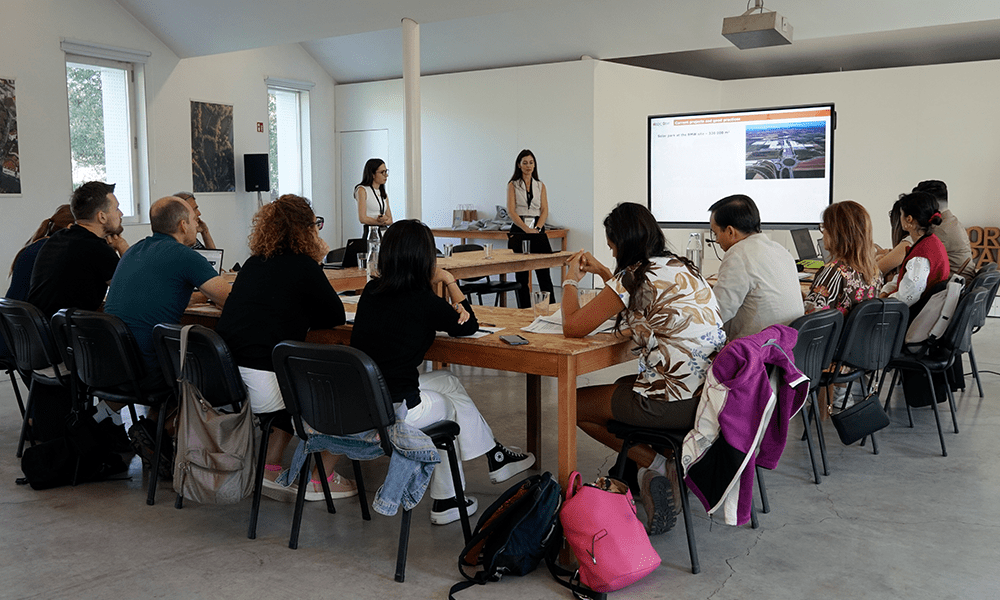

To share effective practices and exchange knowledge, the city organises four training sessions each year for participants. The sessions are led by the city but also by the companies themselves, turning the programme into a peer-to-peer learning space.

“It is a double benefit. For companies, it is communication and visibility. For others, it is inspiration and practical guidance,” says Zachar.

The city will showcase results through media stories, social media and an annual award event.

“We want people to see that this is not just a city project. It is a collective effort by responsible companies that care about their community and the planet,” says Zachar.

A city in action

For Zachar, the most valuable outcome is long-term engagement. “Our goal is not only short-term savings but long-term cooperation. If companies stay in the programme for years, even decades, that is real success.” He believes this approach fills a critical gap in Europe’s climate transition. “There are a lot of commitments but a little less action. We wanted to say: no more promises, let’s focus on concrete actions,” he added.

By asking companies to share real consumption data and be transparent about their results, Bratislava is setting a new standard for accountability. “We don’t punish anyone if they don’t reach every target. What matters is that they act, that they move forward. Because that is how change happens,” Zachar says.

All ten companies from the pilot year plan to continue, and the next edition will open to new sectors such as banking, insurance and manufacturing.

As other Mission Cities put their Climate City Contracts into motion, Bratislava offers a compelling example of how to build a functioning dialogue between city and industry. By aligning business incentives with public goals, the city is creating a model for investment, innovation and shared accountability.

“Without trust and transparency, you cannot influence big companies or even small ones,” Zachar reflected. “But if you build that trust, you can move together. And that is what this is really about.”

Cities Mission in practice

Across the continent, cities are racing to turn the goals of the EU Mission for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities into tangible results. Bratislava’s story shows that the transition will not be driven by policy alone but by partnerships that bring together public purpose and private capability. If cities can open the door to genuine cooperation with business, they will not only reduce emissions faster but also unlock the financial and creative energy needed to reshape urban life for a climate-ready Europe.