Author: Barbara Jarkiewicz

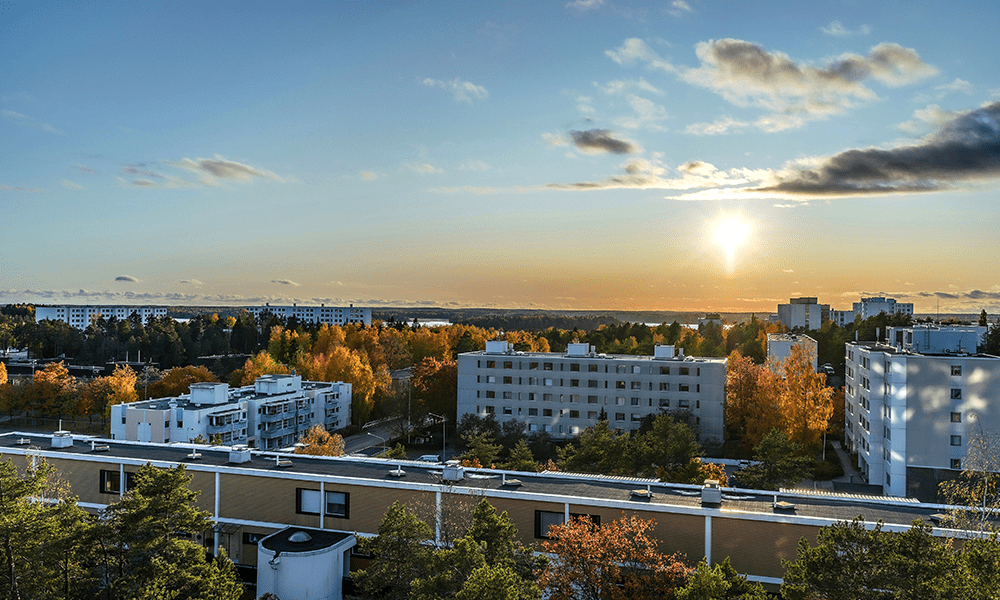

Visitors arriving in Espoo often notice the scenery first. The city sits on 58 kilometres of seashore, with 165 islands and forests around. That landscape is not a postcard backdrop. To protect it, the city has committed to becoming climate neutral by 2030. Its strategy has been to make climate action a shared effort across the city, bringing businesses, civil society and citizens into the work, while developing an investment framework that helps turn green ambition into investable projects.

The scale of the task is stark. Espoo’s target is an 80% cut in emissions by 2030, but updated scenarios show current measures delivering only 60%. The city’s population has almost doubled since 1990 and is expected to double again by 2030, which naturally increases emissions. The Climate Neutral Espoo 2030 Roadmap will be updated in 2026 to reflect the new data and add extra measures.

“Until now, the sharpest cuts have come from district heating, which used to be city’s main source of emissions, where levels had already fallen by 38% last year and are expected to reach zero by 2030,” said Mia Johansson, climate specialist from the City of Espoo.

That shift has not been a solo effort. 75 per cent of residents of this Finnish city live in buildings heated through the district system, which is operated by a private company, Fortum. Johansson is clear that the city could not have delivered those numbers without a shared approach:

“It was only possible because Fortum and the City of Espoo have committed to this transformation that will contribute to Espoo’s carbon-neutrality target by 2030.”

Collaboration as infrastructure

Collaboration is not a new experiment in Espoo. It reflects how the city has developed over the decades. Espoo is home to many company headquarters, universities and research centres. Johansson traces the current work back to that mix.

“The spirit of collaboration with local partners has been part of our culture. Now it has been fully integrated into climate action as well,” she said.

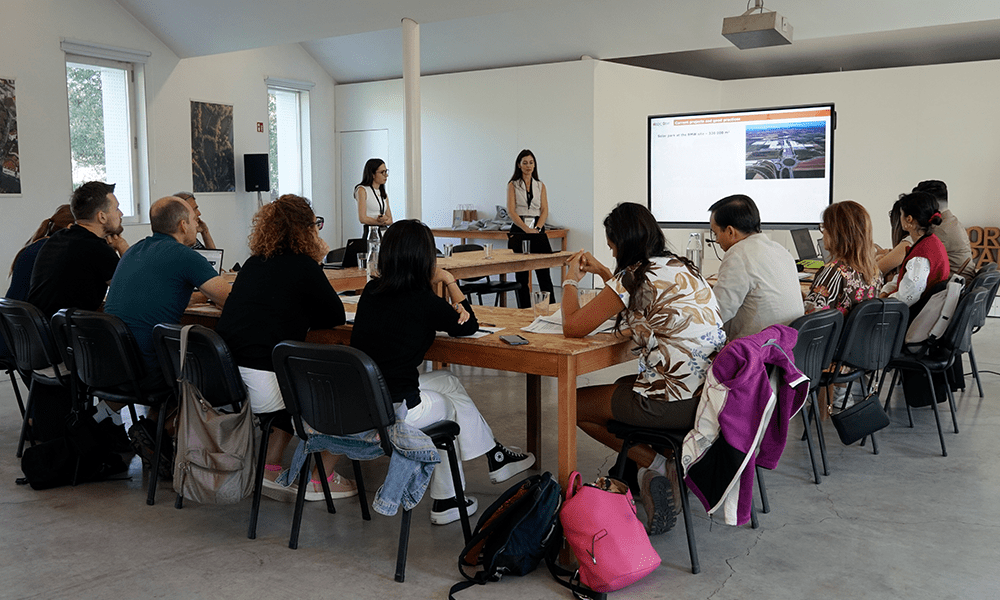

That culture has been formalised through Espoo’s climate partnership, built under its Climate City Contract.

“The city has already established collaboration with 25 different stakeholders, including companies, research institutions and education organisations. The Pilot Cities Programme (PCP) COMET project sits on top of that structure and is designed to deepen those relationships and widen the circle to residents,” Johansson said.

Citizen engagement through civil society

A central part of the COMET project focuses on citizens. The starting point was recognising that infrastructure, on its own, does not do the trick.

“You can build rails, bring more trains, and build metros, but nothing happens if nobody uses them,” Ikävalko said.

The project introduced climate participation activities with civil society actors.

“We decided that if we really want to increase the engagement of citizens, we needed the right partners to do it efficiently. We need civil society in between, that can create their ways for genuine climate action,” Ikävalko said. The city’s role was to enable rather than script every activity.

Together with them, Espoo carried out a series of initiatives that engaged 1,255 residents. One line of work focused on deepening people’s connection with nature and everyday climate choices, from Finland’s first Planetary Garden field station in the Bemböle district, created as a shared learning and action space especially for young people, to mushroom foraging trips that helped residents explore biodiversity and climate-responsible behaviour. Another set of activities brought climate action into public spaces through mending and upcycling workshops in libraries and other venues, promoting circular economy, repair culture and community participation, while bicycle maintenance trainings equipped residents with practical skills for climate-sustainable mobility.

Other initiatives focused on climate literacy and emotional resilience. A Climate Ambassador initiative in upper secondary schools offered lessons on climate change and policy, aiming to increase understanding, reduce climate anxiety and empower youth. Creative writing workshops provided a safe space for people to process climate concerns and explore everyday solutions, while tailored activities for people in mental health recovery used hands-on tasks to support both wellbeing and climate engagement.

This focus on everyday life and wellbeing naturally led the team to look more closely at the direct links between climate action and health.

“Kids and citizens today face a major health issue in Finland. For example, only around 30% of Finnish children do not get enough exercise,” Ikävalko said.

At the same time, thousands of weekly car journeys criss-cross Espoo as families drive children to trainings and matches.

From that point came a sequence of practical steps with local clubs and city departments. The city’s sports and exercise unit held a workshop to look at how clubs could become more sustainable. Then, a roundtable brought together local sports clubs, national federations such as the Finnish Olympic Committee and the Finnish Football Association, as well as experts from the city, to discuss what kind of collaboration and actions are needed to enable a more sustainable sports community and sustainable mobility.

Espoo has since created a web page for sports clubs that includes a challenge to activate children, a step-by-step guide to sustainable mobility principles, and advice on running social media campaigns about active travel.

“Through these pilots, the team has drawn a broader lesson about how to speak to residents. The city and its partners have already applied for a new project with the sports and exercise unit to continue this work,” said Ikävalko.

Feeding back into the climate roadmap

Within the city administration, the Pilot Cities Programme work has directly fed into the next phase of the Climate Neutrality Roadmap. Through workshops with climate partners, Espoo has been gathering ideas for additional measures that could close the gap to its 2030 target and better capture the impact of partner actions.

The climate partnership will continue, with plans to add new partners and co-develop further measures. Espoo has also leveraged the wider Mission Cities network.

The lesson from Espoo is not to replicate every structure but to examine the enabling conditions. The strategic commitment came first and has been kept stable across political cycles. The city then invested time in identifying which actors were crucial for its climate goals and was building trust through regular contact. Civil society groups were treated as partners rather than as an audience. Climate investments were seen as part of an economic strategy rather than a separate agenda. Most of all, the work rests on a simple recognition, as Johansson puts it, “the change is made together in Espoo.”