Author: Ayden Maher

A library that set the tone

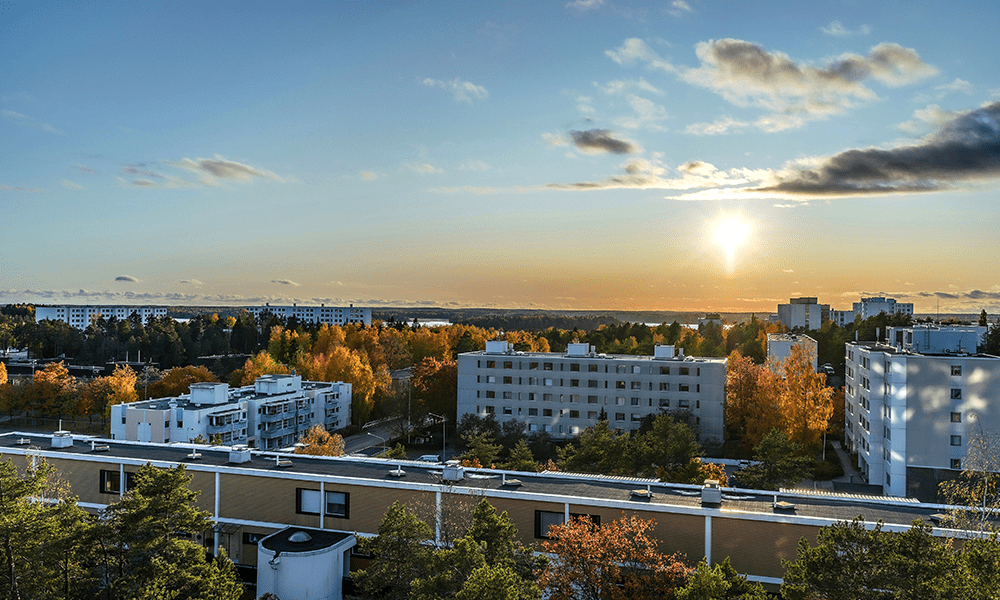

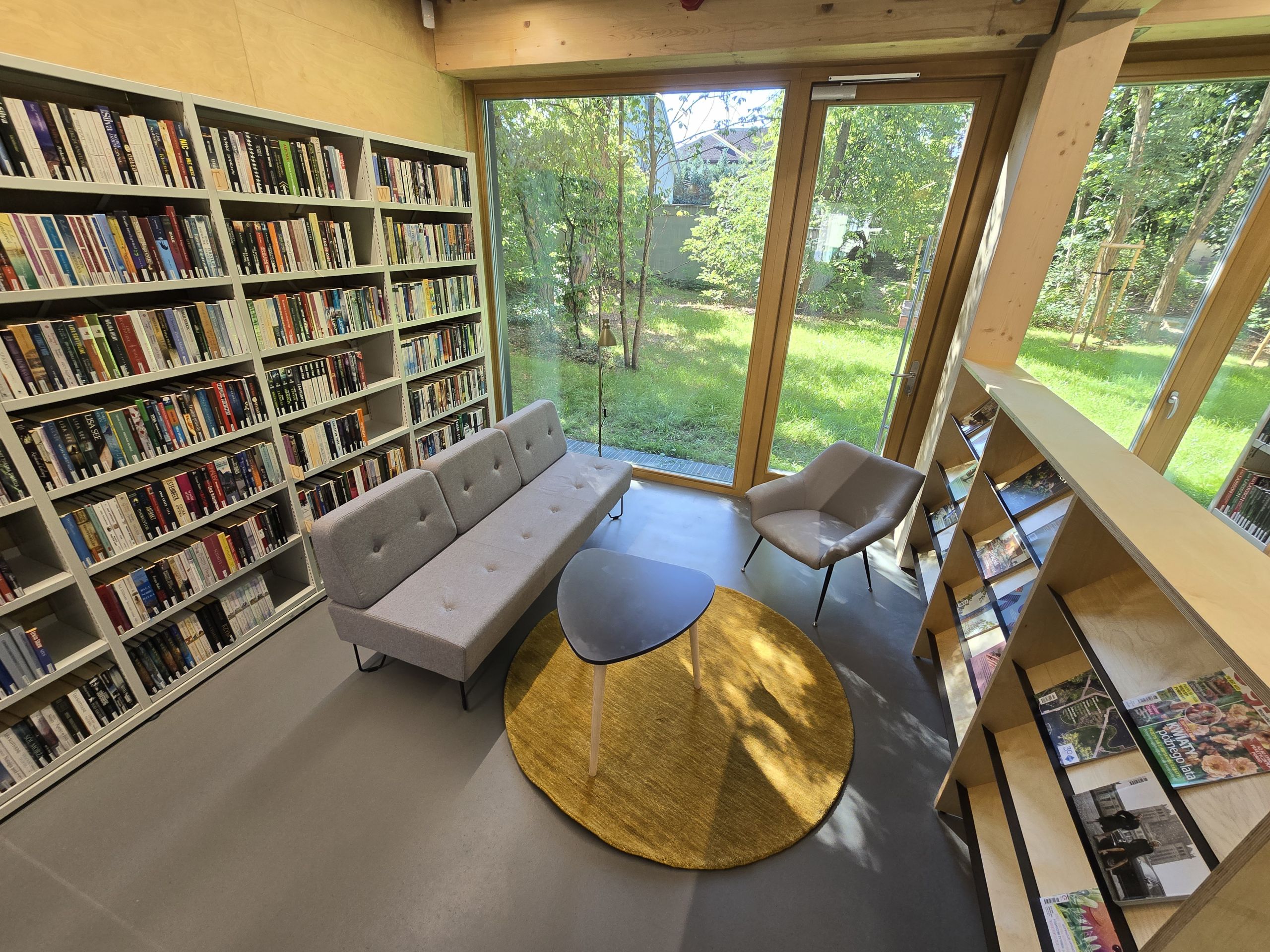

Before it even opened its doors, the new public library in Warsaw’s Białołęka district was winning awards. Designed with solar panels, natural lighting, and spaces shaped by greenery, it became the first municipal building to be certified under the Warsaw Green Building Standard (WGBS). For the city, the library was more than just a local success; it was proof that climate ambition could be translated into tangible, physical spaces.

“We cannot have a strategy that says we will protect biodiversity and then build as business-as-usual,” says Jacek Kisiel, Deputy Director of the Air Protection and Climate Policy Department.

“The Green Building Standard ensures that climate is always part of the decision, not an afterthought.”

© Białołęka District Office, City of Warsaw

From strategy to mandate

The roots of the WGBS stretch back to 2018, when Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski elevated climate policy to a top priority and created a new Air Protection and Climate Policy Department. By 2023, the city’s Green City and Climate Action Plan had set ambitious targets: a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050.

Yet Warsaw’s ambitions are also shaped by its role as one of the European Commission’s Mission Cities, supported by NetZeroCities. In its Climate City Contract, Warsaw pledged to go further, aiming for an 80% reduction in emissions by 2030 in two diverse “lab districts”, Praga-Południe and Ursynów, where new solutions can be tested and scaled citywide. This dual-track citywide 2050 neutrality and accelerated transformation in pilot districts reflects a reality shared across many Mission Cities. While the EU Mission calls for 112 cities to be climate neutral by 2030, most will achieve this in targeted areas rather than across their whole territory.

Against this backdrop, the Warsaw Green Building Standard became a crucial instrument. It translates long-term neutrality goals into binding requirements for every new municipal building.

“The Green Building Standard makes climate commitments operational, ensuring that each new school, library, or cultural centre contributes to our Mission goals.” explains Kisiel

The answer came not only from inside city hall, but also from its citizens. In 2020, Warsaw conducted a civic panel called the Warsaw Climate Panel, bringing together 90 randomly selected residents to deliberate on energy efficiency and renewables. Out of 93 recommendations, 49 were adopted, including a call for a green building standard.

“This gave us a very strong mandate,” Kisiel recalls. “The Civic Panel is maybe the one and only form of direct democracy we have in Poland. When citizens told us they wanted this, we had an obligation to deliver.”

Adopted by ordinance of the Mayor in late 2024, the WGBS became mandatory for all city-owned buildings from July 2025. It is now a central piece of Warsaw’s climate governance.

Building a coalition

Introducing the standard was not without risks. Higher upfront costs for heat pumps, green roofs or retention basins could have led to resistance from investors. The city also worried about adding new procedures in a European context pushing for faster, leaner processes.

“We were afraid investors would say, ‘why make our projects more expensive?’” Kisiel admits. “So we built a coalition from the start. We invited supportive investors to be our critical friends. We met with every district mayor. We made sure we had political support at deputy mayor level. That support was crucial.”

The city also introduced a ten-month grace period before the standard became binding, giving time for training and dialogue. Kisiel and his colleagues are currently visiting every district, explaining that the standard would make projects easier to manage.

© Białołęka District Office, City of Warsaw

“We told them: put this in your tender and architects will know what to do. It actually reduces your work.”

To their surprise, the response was overwhelmingly positive. “Instead of complaints, we found enthusiasm. Some investors even paid more to architects to make their projects compliant. They wanted that certificate. That was a turning point.”

More than rules: a tool for education

The Warsaw Green Building Standard is not a single checklist but a framework built around six key areas: greenery and plot development, water management, energy efficiency, sustainable mobility, circular materials, and health and comfort. Each project must meet core obligations in these areas and then select additional solutions to raise its ambition. That flexibility means that very different kinds of investments, such as a neighbourhood library, a school, or a park-and-ride facility, can all be designed in line with the standard.

In practice, this means requirements that go beyond national law. Every new building, for example, must calculate a Blue-Green Infrastructure Index and ensure stormwater must be retained and absorbed on-site avoiding discharge into the sewage system. Educational buildings are required to install mechanical ventilation with energy recovery, which cuts heating costs and improves indoor air quality. Parking facilities certified under the WGBS now use permeable paving materials and integrate nature-based retention solutions, such as “dry rivers” or rain gardens, alongside photovoltaic panels and heat pumps.

For Jacek Kisiel, the most important effect of these requirements is not only the technical performance of the buildings, but the learning process they trigger.

“When investors read the list of materials with lower carbon footprints, many told us, ‘we never thought this was important,’” he recalls. “It’s not only a technical standard. It’s environmental education for investors, architects, and even citizens.”

That educational role quickly became visible. In one controversial development, citizens opposing the project challenged the investor: if you are truly environmentally friendly, prove it by showing compliance with the WGBS. The fact that residents knew of and invoked the standard was, to Kisiel, “amazing. It shows people are aware of the tool and see it as a guarantee of quality.”

Early results and ripple effects

Even before becoming obligatory, five city projects voluntarily applied and received certification. The Warsaw School of Economics became the first non-municipal institution to secure certification for a new pavilion. Other flagship projects include the Białołęka Library, the Centre for Environmental Education in the City Forests, and the eco-park-and-ride facility at Połczyńska, which incorporates permeable materials, PV, and nature-based water retention systems.

Recognition has come quickly. The standard has already won awards in the Innovative Local Government competition and from the national real estate sector for raising quality in construction. The certified projects themselves are also receiving architectural prizes.

Perhaps more importantly, Warsaw’s approach is spreading. Wrocław, Katowice, Bratislava, and Poznań are now exploring their own standards, drawing directly on Warsaw’s Green Building Standard.

“Even if they are not part of the EU Cities Mission, we want to inspire them,” Kisiel says. “If they want to adapt our model, we are ready to help.”

© Białołęka District Office, City of Warsaw

The road ahead

The next step is to extend the standard to retrofits a daunting challenge in a city full of protected heritage buildings. But Warsaw is determined.

“Retrofitting may be even more important than new buildings,” Kisiel argues. “It is where we will save the most energy, but it requires careful design and new solutions.”

Private sector uptake is another priority. While not yet mandatory, the city hopes that developers will increasingly see certification as a mark of quality and competitiveness.

“The WGBS certificate confirms the unique climatic quality of a building, not only in Warsaw but on a European scale,” Kisiel notes.

Changing how a city thinks

For Kisiel, the real innovation of the WGBS lies not only in its technical requirements, but in how it changes mindsets.

“The innovation is not that we are using green roofs or solar panels,” he says. “The innovation is that through legislation we change the way we think about buildings about designing, constructing, and operating them.”

That change is already visible. From award-winning libraries to everyday schools and public services, Warsaw is proving that climate neutrality is not just a distant goal but a principle shaping daily investment decisions.

“We cannot have strategies on paper and business as usual in practice,” Kisiel concludes. “The Green Building Standard ensures that every new brick we lay brings us closer to climate neutrality.”