Author: Ayden Maher

Stories from Pilot Cities: Marseille is one of the 112 cities participating in the EU Mission to deliver 100 climate-neutral and smart cities, and the Pilot Cities Programme – a component of the Mission that focuses on exploring and testing pathways to rapid decarbonisation over a two-year period.

How businesses and neighbourhoods are building a climate movement together

When Marseille joined the Pilot Cities Programme, it wasn’t to add a few more environmental projects to its to-do list. The ambition was bigger: to change how climate action happens in the city, by making residents, businesses, and local organisations co-creators of a greener, fairer future.

“We are Mediterranean, we are resilient, and we are transforming, but we are doing it with people,” says Camille Spaeth, who coordinates the programme for the city.

That people-first vision runs through Marseille’s new Climate City Contract, its first comprehensive climate strategy. Drafting it brought a central barrier into focus: what Camille calls the city’s “inaction triangle.” “Citizens say companies or the public administration should act.“

Companies say the administration should act. “We all have our part to play,” she explains. “Many people are already acting, it just wasn’t visible. We wanted to make those efforts visible, connect them, and show that we can act together.”

The Pilot Cities Programme has given Marseille the resources to do just that, embedding facilitators in neighbourhoods, mobilising business networks, and creating platforms where different actors meet, work together, and change the system from within.

From bus lines to shared gardens

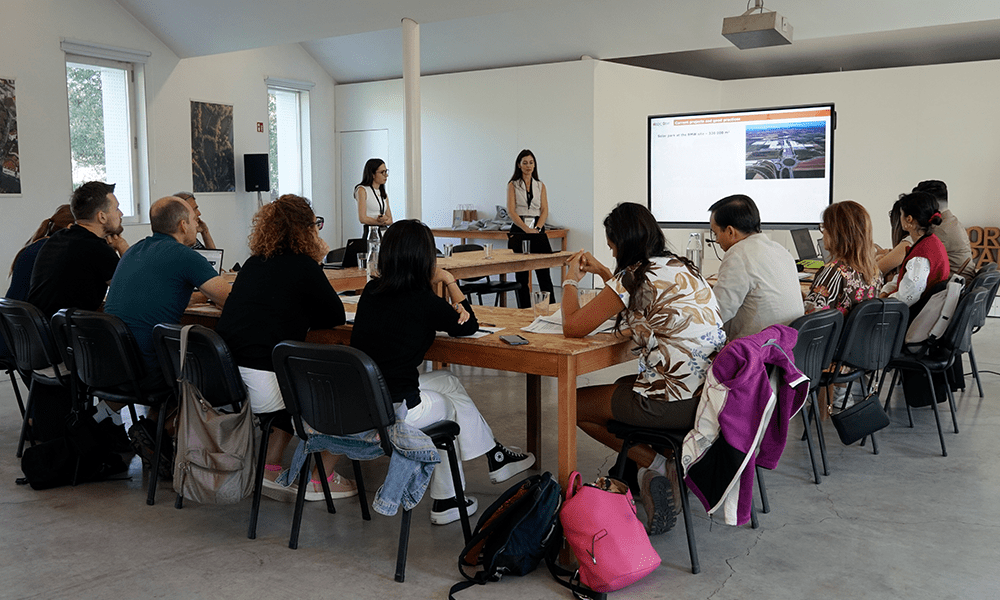

The most visible part of this transformation unfolds in Marseille’s neighbourhoods. Rather than asking residents to adapt to a one-size-fits-all plan, the city placed three facilitators directly within areas that each face their own distinct challenges, from dense historic quarters to suburban districts and neighbourhoods on the urban fringe. By being present on a day-to-day basis, the facilitators ensure that local priorities inform the broader climate strategy, transforming scattered concerns into collective action.

Employed by the Ligue de l’Enseignement, a civic association already working with residents, they are regarded as trusted allies.

“Because they are from an association, close to inhabitants, people talk to them,” says Camille. “That trust is essential.”

Facilitators meet people where daily life unfolds outside schools, in social centres, or around shared meals and listen first. In one northern district, residents revealed how cut off they felt since an evening bus had been cancelled. With support, they drafted letters to elected officials and spoke to the media. Within three weeks, the bus was reinstated after a year of absence.

For residents, it was more than just a transport issue. It showed that collective action could change daily life.

“It was a very big success” says Camille. “People saw the results of organising together.”

In the city centre, meanwhile, neighbours are creating a shared garden that will strengthen social ties, enhance biodiversity, and provide a shaded refuge during hot summers. In each case, the method is the same: start with local priorities, make them visible, and connect them to the broader climate transition.

Pioneering businesses

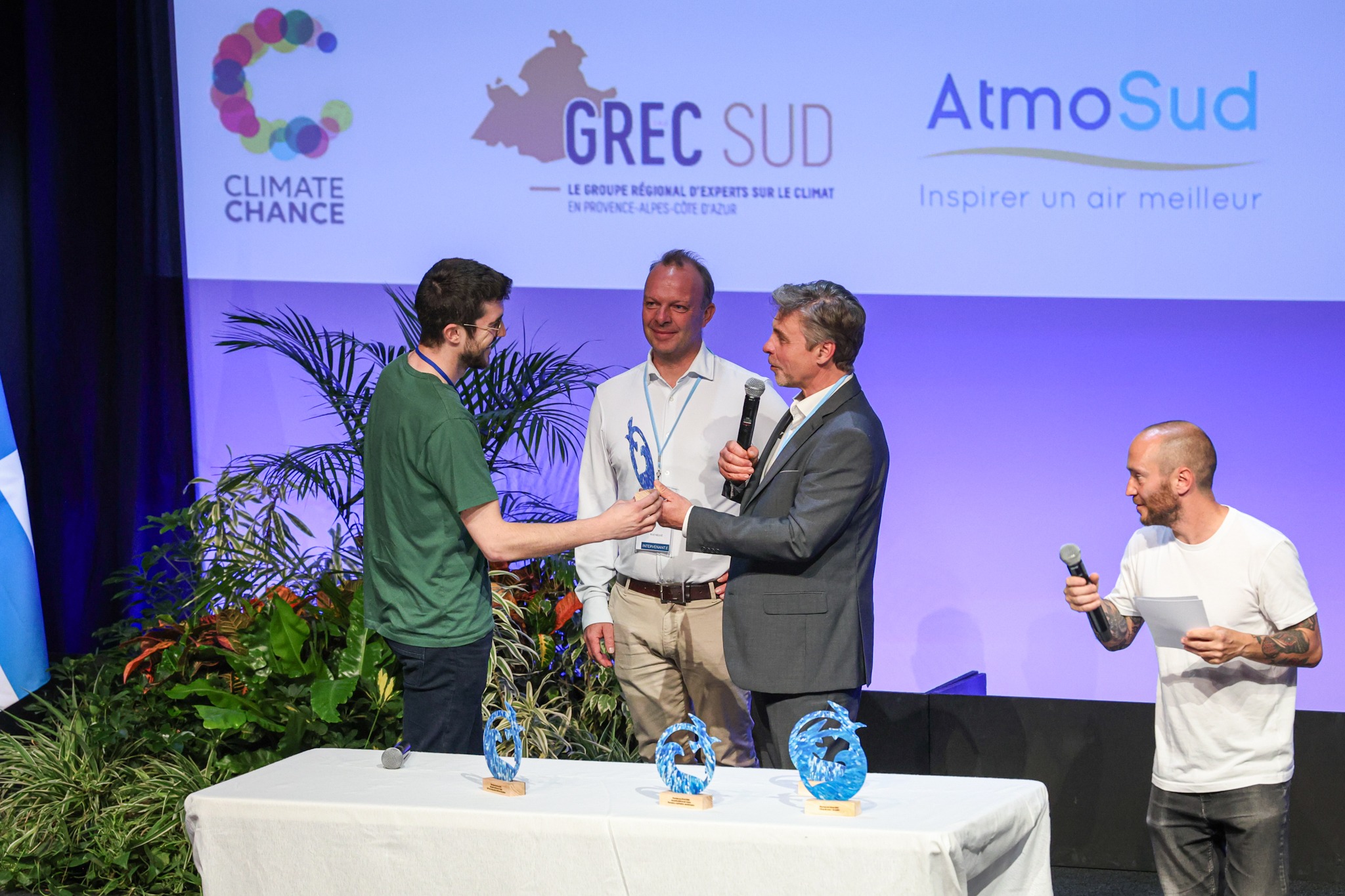

In parallel, Marseille is mobilising its business community through three enterprise networks. Their task is to integrate climate action into everyday business practices, from developing employee mobility plans that encourage cycling and public transportation, to installing solar panels, to shifting deliveries from vans to cargo bikes.

The city, with its partner Atmo Sud, also celebrates leaders through the Climate Pioneers Trophies, awarded this spring to six organisations. Among them was La Boîte à Vélo, which helps companies integrate cargo bikes into their logistics chains, and Friche Belle de Mai, recognised for transforming a vast industrial site through large-scale revegetation and climate adaptation measures. Ninety was honoured for raising awareness about electronic waste by showcasing how devices can be repaired and reconditioned. At the same time, Le Présage demonstrated a new model for zero-petroleum, solar-powered, local food. Sénova received recognition for its work on energy renovation and greening of residential buildings, and the People’s Choice Award went to Massilian Sun System, a cooperative enabling residents to co-finance rooftop solar installations combined with roof insulation.

“The trophies make the invisible visible,” Camille explains. “They highlight the virtuous actions companies are already taking to inspire others and create connections.”

© Ville de Marseille

© Ville de Marseille

When the pieces interlock

On their own, each story, a bus reinstated, a garden planted, a workplace mobility plan drafted, might look modest. But together they show a new way of working: facilitators and business networks turn neighbourhood demands into projects, link them with city services, and make them visible through platforms like the Climate Pioneers Trophies. In this way, public transport becomes more than mobility infrastructure; it is an enabler of social cohesion and public wellbeing. Green spaces cool streets while also building community ties. Business-led solar and mobility plans reduce emissions and improve the quality of life for employees. It is the combination of these co-benefits, multiplied across the city, that signals a real shift in how Marseille approaches climate action.

Facilitators route community priorities directly to the right municipal services and elected officials. Business networks normalise decarbonisation steps across dozens of firms at once. City coordination and grant-making embed this method into policy.

The glue is in the convergence. “We didn’t initially know how citizens and companies would connect,” Camille admits. “Now they’re asking to work together on mobility, on bike lanes, on greener spaces.”

The same shaded lunch spots employees want become the cool refuges residents need in heatwaves; the cycle lanes commuters ask for are the safe routes parents want around schools.

Scaling up and sharing out

With the pilot now at its midpoint, Marseille is already planning for scale. Aix Marseille University will support by highlighting what worked or not. Facilitators trained through the programme are being linked with existing neighbourhood workers funded under France’s programmes dedicated to vulnerable neighborhoods, ensuring the climate engagement method will continue after the pilot ends. And the Climate Pioneers Trophies will continue, with more targeted outreach to ambitious firms.

“It started in three neighbourhoods,” Camille says, “but the goal is to take the method citywide.”

The approach is already drawing attention abroad. Marseille has shared lessons with its Spanish twin city, Sant Boi de Llobregat, which will explore how to adapt the trophies model to its context.

“What we can share is how we did it,” Camille reflects. “Rely on existing associations; focus on very concrete projects; get a direct link with citizens.”

© Ville de Marseille

For Camille, the most meaningful result is not a single project but a new coalition.

“Citizens and companies are coming to us with the same demands now,” she says. “That’s when you know a transition is taking root when people who didn’t work together before are asking to act together.”