Author: Barbara Jarkiewicz

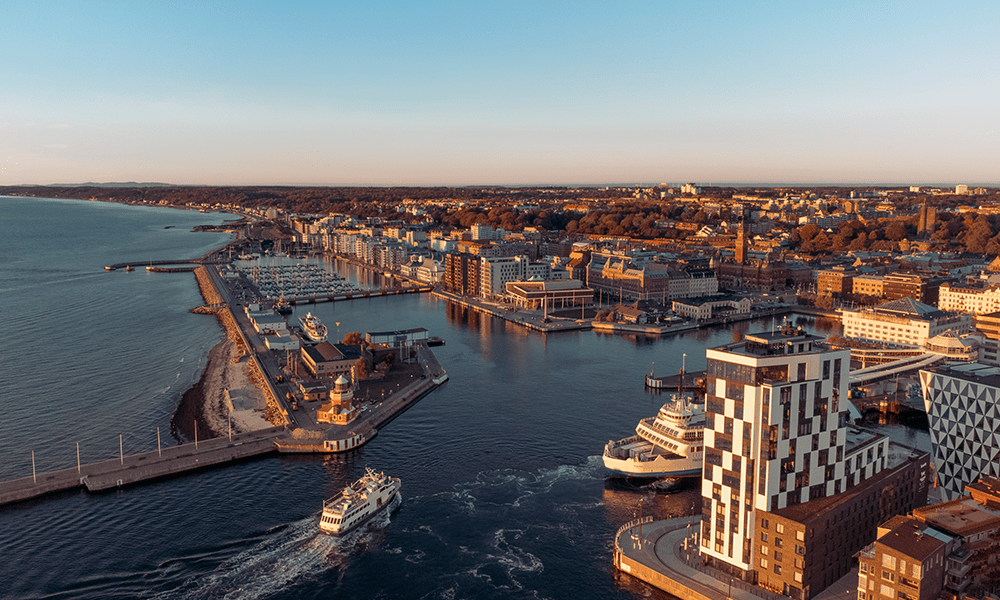

Stories from Pilot Cities: Helsingborg is one of the 112 cities participating in the EU Mission to deliver 100 climate-neutral and smart cities, and the Pilot Cities Programme – a component of the Mission that focuses on exploring and testing pathways to rapid decarbonisation over a two-year period.

Helsingborg is taking on one of the toughest climate challenges in Europe by cutting emissions from the construction sector. The Swedish coastal city is transforming its Oceanhamnen district into a living laboratory where new ways of designing, building and managing materials are tested in real time. The goal is to show that climate neutrality in construction can be achieved through collaboration, data and courage.

In Helsingborg, innovation is part of everyday life. The city has turned experimentation into policy, rewarding those willing to test and learn. Every year, the municipality even celebrates “the best mistake of the year,” an award that honours the value of failure in driving progress.

“Mistakes are where learning happens,” says Milou Mandolin Strandberg, Climate Strategist/Process Manager. “We dare to test and to fail, but also to scale up what already works.”

That mindset now fuels one of Helsingborg’s most ambitious projects yet. Through the Pilot Cities Programme’s Co-Build initiative, under NetZeroCities, the city is addressing the emissions embedded in buildings and construction materials, which often fall outside traditional carbon accounting.

“When it comes to city emissions, we have quite a lot of control. But emissions linked to building and construction are trickier to work with. They are not part of the scope one and two categories that most climate goals focus on, yet we want to tackle all of them holistically,” said Mandolin.

Building the Future in Oceanhamnen

Oceanhamnen, a former industrial port, has become the focal point of Helsingborg’s experiment. The district now serves as a test site where the city and its partners apply Life-Cycle Assessment methods to track emissions from the production of steel and concrete, the transport of materials, and on-site construction work.

© City of Helsingborg

The Co-Build project focuses on three interconnected processes. One examines emissions from new buildings, another studies construction activities such as excavation and machinery use, and a third looks at the earliest planning stages when design decisions shape future carbon footprints.

“We meet regularly with people from different departments, municipal companies and our partner IVL, the Swedish Environmental Research Institute. We are learning from each other and developing common methods,” explains Martina Oxling, Project Manager, CoBuild NetZero.

One of their main achievements is the creation of calculation instructions that define how emissions should be measured and set annual limit values up to 2030. These limits will guide future permits and procurement decisions across the city.

“We have already published the first version and invited feedback from local companies. Sixteen organisations in the building and construction sector have joined our discussions. They really feel ownership of what we are developing and want to use it in their daily work,” said Oxling.

The project also tests practical tools that integrate emission calculations into daily planning routines, allowing engineers and architects to see the climate impact of their choices before construction begins. Oceanhamnen acts as a living lab where these tools are tested, adjusted and shared.

“We would like to open up our city as a test bed. We are not just talking about ideas. We are doing things together and learning from them,” said Oxling.

Collaboration as Climate Strategy

Helsingborg brings in local developers, businesses and universities to map and reduce risk and uncertainty for businesses, develop common standards, and test climate-neutral procurement practices. The aim is to turn climate-neutral construction from an exception into the standard practice.

“Helsingborg is good at involving different external actors,” Oxling says. “The key is that we listen. We do not run campaigns to convince people. We talk to them, understand how they work and see how we can help each other. We all need to make this transition.”

This spirit of collaboration extends beyond the municipality. Partnership lies at the heart of Helsingborg’s approach. The city works closely with other cities such as Malmö and Lund to align construction standards and share findings. Each city focuses on a different aspect of the problem while learning from one another’s results.

“We have found a common ground where we can really add to each other’s work and co-create in a valuable way. It takes more time when we cooperate, but in the long run it is really worth it,” Oxling. explains.

A Systemic Approach to Change

Co-Build is closely tied to Helsingborg’s Climate City Contract, developed through the NetZeroCities programme.

“Our Climate City Contract is part of our shared roadmap. The Pilot Cities Programme is where we test the tools. Every pilot we run is part of this bigger integrated effort towards our 2030 goal,” says Mandolin.

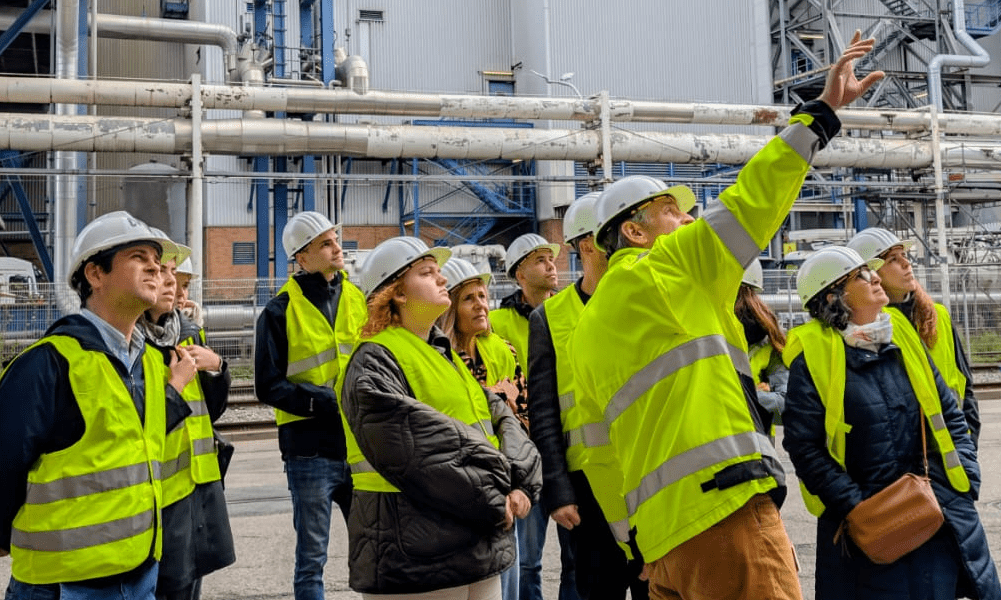

© City of Helsingborg

That goal is demanding. The city plans to reduce construction-related emissions by half by 2030 while continuing its long-term path to climate neutrality. Helsingborg already has a strong record. Since 1990, it has cut total emissions by more than 55 per cent even as its population has grown by 40 per cent. The city has switched to renewable energy, built Sweden’s largest biofuel plant and introduced one of the world’s first sustainability-linked municipal bonds. Each step has built trust that systemic change is possible.

“It is easy to think that the solution is technology. But it is much more about culture and courage and how powerful trust can be. When people feel that their ideas matter, change happens faster,” says Mandolin.

Learning to Lead

To strengthen that culture of trust, Helsingborg has introduced a learning process within the Co-Build project, supported by the city’s Innovation Fund. The programme brings together a group of change-makers from across municipal departments, partner organisations and private companies. They meet for a series of eight workshops focused on mindsets, tools and real projects that can speed up the transition within the construction sector.

“It is amazing to see how people learn from each other,” says Oxling. “In the beginning, they are hesitant, but after a while, they are collaborating and creating together.”

The city is also exploring regulatory sandboxes in collaboration with researchers and consultants. These allow specific rules to be tested or adjusted on a small scale so that new solutions can be developed safely.

“We are trying to see how we can work with regulations in a more flexible way. It is about doing something small and learning from it,” Oxling says.

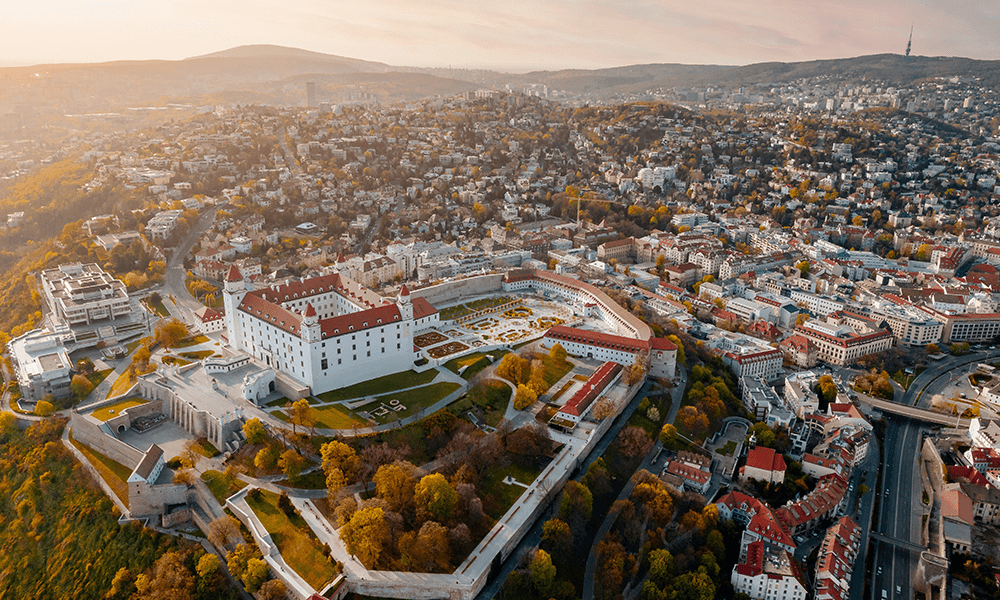

© City of Helsingborg

From Pilot to Long-Term Transformation

For Helsingborg, climate neutrality is not a sprint. It is a long journey that will continue well beyond 2030.

“This is not just paperwork. These pilots are engines to scale up successful solutions and attract green investments. The Pilot Cities Programme is one milestone in a much longer journey,” says Mandolin.

That journey has already turned Helsingborg into one of Sweden’s most dynamic climate leaders. With 150,000 residents, the city is large enough to act at scale yet small enough to stay flexible and coordinated.

“We started working on environmental issues back in the 1980s. What is different now is that we are doing it together, across all sectors,” says Mandolin.

Helsingborg offers a concrete example of systemic change in motion. It shows that progress can grow from cooperation, shared learning and the willingness to keep experimenting.

“We really do want to invite others to test, develop and scale solutions with us, to contribute to climate neutrality while creating a city where people thrive and enjoy life,” said Mandolin.