Author: Ayden Maher

In the heart of London, Westminster is home to a diverse community of residents, institutions, and businesses, presenting a uniquely layered challenge for the climate transition. At first glance, it bears little resemblance to cities like Leuven in Belgium or Lund in Sweden. But through the Twinning Learning Programme, these cities are united by a common goal: to transform how urban areas are heated and to do so in a way that brings long-term benefits to local people.

What happens when cities with vastly different contexts come together to tackle one of the most complex aspects of climate action—heat transition? Through shared visits, open dialogue, and practical exchanges, Westminster, Leuven, and Lund began to reimagine what’s possible. Not by following a single path, but by learning from each other’s approaches, questioning assumptions, and discovering new ways to put people at the centre of change. The result isn’t a fixed blueprint—but a growing sense of how collaboration can unlock climate solutions that are not only effective, but deeply rooted in local realities.

A new direction for heat networks in Westminster

Westminster faces a formidable climate challenge. A large amount of its emissions come from energy use in buildings, and its dense, historic built environment limits the options for simple retrofit. In response, the Council is exploring how it can develop neighbourhood-scale heat networks, building on the flagship South Westminster Area Network (SWAN) project being developed by the SWAN Partnership; a joint venture between Hemiko and Vital Energi. The SWAN network has the potential to be the UK’s largest heat network and could supply low carbon heat to around 1,000 buildings, powered in part by waste heat sources such as the River Thames, London Underground and sewer network.

Westminster has begun identifying additional zones through its Local Area Energy Plan where neighbourhood scale systems could be delivered in an approach inspired by Leuven’s “lighthouse district” model. Key to this approach is ensuring that technical design happens alongside meaningful engagement with communities, building trust and visibility for a largely invisible infrastructure.

Alex Downes, Green Fund Manager at Westminster City Council, sees the value.

“For our council, the benefit of collaboratively exploring heat networks is the shared learning and the opportunity for us to find ideas and concepts that we can see working in other places,” he said. “It’s helped us bring together teams from across the council to understand what Lund and Leuven have done and how this may be applied borough-wide.”

To integrate the change into Westminster’s delivery model, the Council has formalised an Energy Network Forum, bringing together a diverse range of stakeholders, including developers, government representatives, academic institutions, large landowners, and residents.

The Forum meets quarterly and has hosted dedicated training sessions and peer learning workshops to build capacity around heat network delivery. Following the success of the Twinning Programme, where best practices were demonstrated through on-site visits.

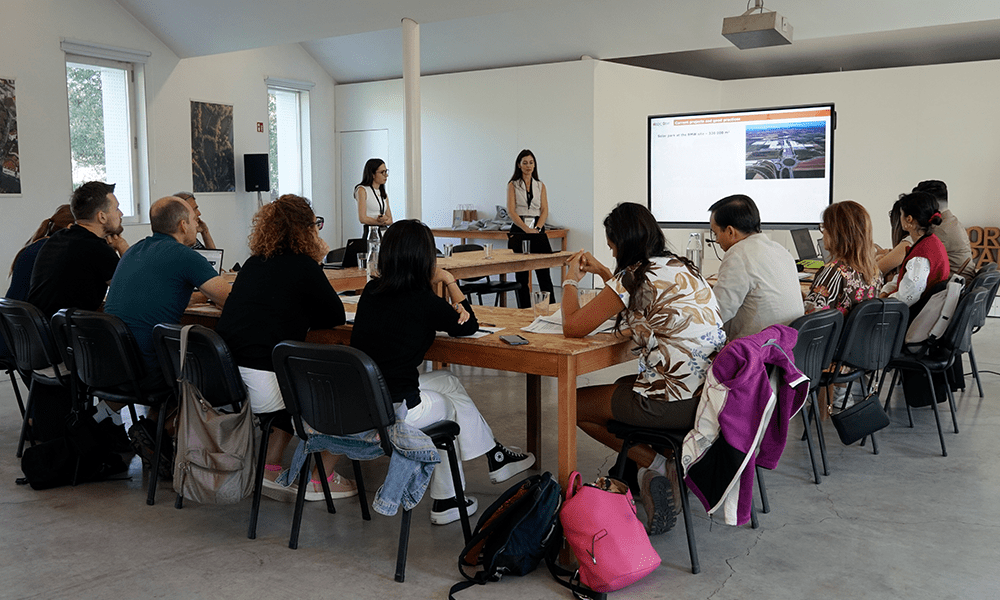

Learning through contrast: Leuven’s response

For the City of Leuven, the approach in Westminster sparked new thinking around speed, governance and citizen engagement. Leuven has already established living labs across three pilot districts, each testing different models of heat decarbonisation. However, the speed at which the heat project in Westminster has been developed and commissioned impressed.

“Westminster’s swift progress stood out,” said Marie Vanderlinden, Project Coordinator for Green Heat in Leuven. “It’s been a compelling example of strategic focus and speed.”

Westminster’s use of high-temperature networks to accommodate heritage buildings also resonated with Leuven, which faces similar technical constraints in its historical quarters. But the most significant shift came from observing how Westminster frames its climate strategy not just around carbon emissions, but around citizens.

Through programmes like North Paddington, which seeks to address social and environmental inequalities while introducing clean energy solutions, and its Westminster Climate Fund, which connects funding to organisation-led climate action, Westminster demonstrates how social equity, regeneration and climate action can go hand in hand.

“The idea of screening neighbourhoods for vulnerability as a starting point, or linking engagement to visible value as Westminster does, offers entirely new entry points for us,” Marie added.

These insights are now being fed directly into Leuven’s strategy for designing a municipal heat company and rethinking engagement mechanisms for its City Climate Contract.

Lund’s role in scaling ambition

In Sweden, Lund’s involvement in the Twinning Learning Programme focused on building systemic momentum, primarily through governance and green finance. The city has pioneered the use of municipal green bonds, investing over 3 billion SEK in retrofitting and clean energy since 2017. It has also established a new Climate Economist post to explore financial pathways for its green transition.

This approach helped Westminster think differently about how to fund its pipeline of clean energy projects. Alongside its internal resources, such as the Westminster Climate Fund, the Council has formed a new Net Zero Partnership with King’s College London to explore innovative green financing tools.

“When we exchange ideas, we see solutions,” said Tommy Bengtsson, Project Manager for CoPilot Lund “The programme helps us build momentum not just as a city, but together with businesses and other actors. It opens windows to finance and connects us to the broader European movement.”

“You can see the difference between cities that learn and those that don’t; they end up as late adapters and pay the cost,” Bengtsson said. “But when you connect cities and share experiences, you gain strength together. You overcome obstacles together.”

Collaboration that continues beyond the programme

The exchange has already had visible impacts. In Westminster, lessons from Leuven and Lund have shaped how heat projects are prioritised, how governance structures are framed, and how residents are brought into the conversation early.

Leuven is adapting Westminster’s approach to its municipal heat plans and developing new strategies for engaging citizens with tangible benefits. And Lund continues to lead at the intersection of finance and governance, coordinating workshops that support other cities on similar journeys.

“This has helped our local authority develop as a team,” said Alex Downes. “I’d recommend Twinning Cities from multiple perspectives—not just for the technical insights, but for the chance to grow together.”

Now open: Call for Twin Cities Applications

The next round of the Twinning Learning Programme is now open for applications. Municipalities from EU Member States and Horizon Europe–associated countries are encouraged to apply by 12 September 2025 at 17:00 CEST.

Participating cities will be matched with pioneering Mission Cities for a 12-month exchange. Through workshops, site visits and peer learning, the programme helps local governments co-develop responses to shared climate challenges while building long-term relationships with fellow climate leaders.

About the Twinning Learning Programme

The Twinning Learning Programme is a flagship initiative, facilitated by NetZeroCities, designed to foster deep peer exchange between cities across Europe. Throughout 12 to 20 months, Twin Cities work closely with Mission Cities learning from their implementation of Climate City Contracts and co-developing strategies tailored to their local context.