Author: Barbara Jarkiewicz

Stories from Pilot Cities: The Hague is one of the 112 cities participating in the EU Mission to deliver 100 climate-neutral and smart cities, and the Pilot Cities Programme – a component of the Mission that focuses on exploring and testing pathways to rapid decarbonisation over a two-year period.

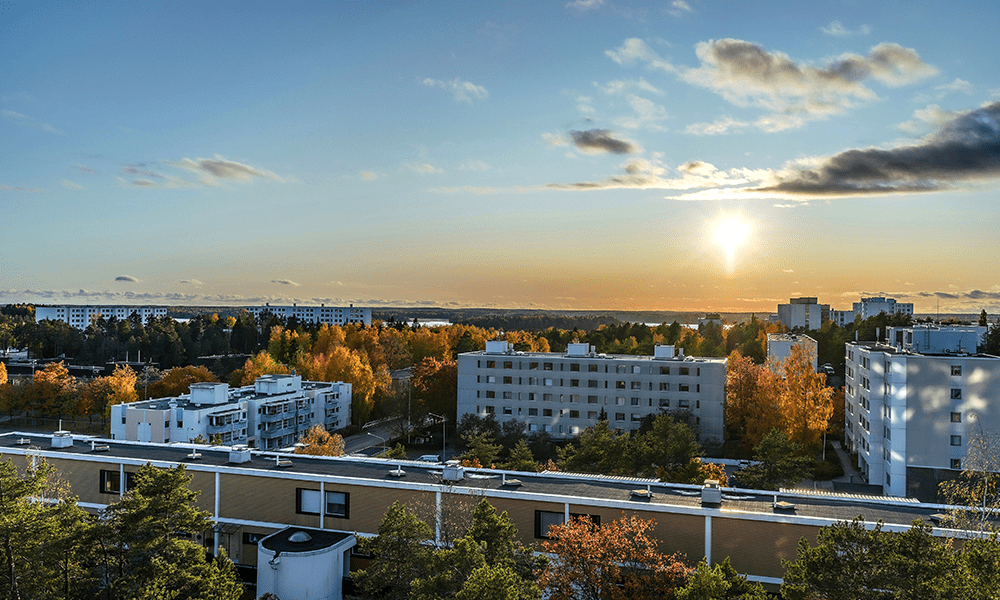

When Petra Bijvoet from the City Hall talks about The Hague, she speaks with the urgency of someone who knows that time is running out. “We’re the most densely built city in the Netherlands,” she says, “and we sit right at sea level. If the sea rises, we’re one of the first to feel it.”

But the city’s challenge goes far beyond climate vulnerability. Its population is a mosaic of more than 180 nationalities, spread across tightly packed urban districts. It’s a place of contrasts that needs a heat transition strategy that works for everyone.

That’s what made The Hague’s involvement in the Pilot Cities Programme so pivotal. As one of seven Dutch municipalities, The Hague embarked on a journey not just to decarbonise its neighbourhoods, but to explore a fundamental question that haunts cities across Europe: how to build the future when the present is full of legal uncertainty, rising costs, and the challenge of citizen trust? Their shared mission: design investment platforms that can unlock funding for neighbourhood energy upgrades, with district heating as the backbone and citizens on board.

© The Hague

“We knew district heating was the most economic option for many districts in a city like ours,” says Bijvoet, the Hague’s strategic advisor on energy transition and project leader for the Dutch cities pilot District Investment Platform. “But when we looked from the citizen’s perspective, especially vulnerable households, they see their energy costs rise, due to high connection costs to the grid and high fixed heat prices”.

The Promise of Heat and a Pragmatic Pivot

The Hague aimed high, planning to connect up to 80,000 homes to one new heat grid, under the prevailing heat law. But as business cases were developed with both public and private partners, the city faced high risks and costs related to extended regulation, infrastructure, and affordability. Investor confidence wavered. Progress slowed.

“The new heat law had been postponed again and again, which caused a stand-still” Bijvoet explains. “Private partners saw the uncertainty and in Utrecht for example, they walked away.”

© The Hague

Instead of pausing efforts, The Hague adapted. The city began experimenting with smaller, more manageable local heat grids. These mini grids would connect about 500 homes each to a temporary but sustainable heat source, preparing the ground for future integration into a larger geothermal powered district heating system.

“We started working and thinking as if the new heat law was already in place.

It’s what we call the ‘inloopoplossing’” Bijvoet says. “We start small, use temporary heat solutions, and eventually connect them to the larger grid with a geothermal heat source once it’s feasible.”

As a result, a letter of intent was signed between the city, the local housing corporation and the district heating company. Despite challenges, including grid congestion, the dialogue and coordination established laid the foundation for future implementation.

Neighbourhood realities

The Hague’s Mariahoeve district, chosen for the pilot, is a case study in the kind of complexity most European cities must navigate. The district is home to 83 homeowner associations (VvEs), each a legal entity with its own governance, finances and priorities.

“Some apartments are well insulated, others, in the same building, are still drafty. Some homeowners are elderly and economical, others are eager to invest in sustainability,” says Bijvoet.

Any decision to retrofit requires supermajorities and, often, personal savings that many households simply do not have or when households do have savings, they have other goals then energy transition or insulation. To move forward, The Hague had to do what few cities have dared: open transparent, data-driven conversations with every VvE involved, backed by tailored building assessments and proposed tailor-made advice.

While neighbourhood pilots took shape, The Hague and its peers lobbied other power centres: the Dutch parliament. In July this year, parliament finally adopted the Collective Heat Supply Act, which then needs to pass the Senate. In all likelihood, the new law will be into force in January 2026. The statute flips control of heat networks, requiring a majority public stake and new financials models with capping tariffs to protect households.

© The Hague

For The Hague, the law removes a major cloud. The city is setting up a public heat company slated to break ground next year and begin hooking up homes by 2029. Eindhoven has recently already set up a public heat company.

Finance with purpose

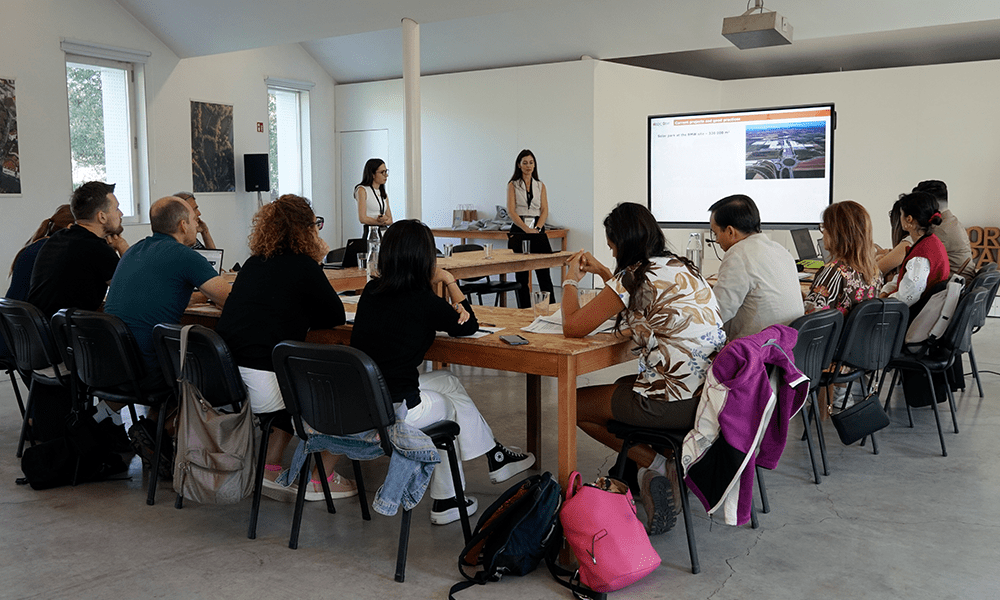

One of the core goals of the Dutch pilot was to develop district investment platforms, blending public and private capital to fund local sustainability transformations.

“Every Dutch pilot city had their own approach. Utrecht developed a slink dashboard to make financial streams and costs visible in order to facilitate discussions with stakeholders within the district. While Groningen focused on aligning energy transition with social goals ,” Bijvoet says. “It’s about aligning different funds, different departments, different ministries, private parties, each with their own rules and risk management.”

© The Hague

For the Dutch cities, this meant something bold: convening the Ministries of Housing, Economic Affairs, and Sustainable Growth, alongside institutional investors, the national heat fund, and even the European Investment Bank. As a result, The Hague, is still exploring innovative financing models, including building-linked loans, which are tied to the property instead of the individual homeowner.

“The idea is simple: don’t saddle people with personal debt. Link the loan to the building, so the climate transition doesn’t punish the resident after moving,” Bijvoet explains.

This concept is still under development, but the conversations and partnerships it has initiated are creating the momentum needed to unlock capital.

A human-first approach

The Hague’s energy transition is also about community. “We didn’t just want to connect pipes,” Bijvoet says. “We wanted to build trust.” That meant organising thematic festivals, offering one-stop shops and training energy coaches to engage citizens directly. Most significantly, the city employed external facilitators to ensure citizens collectives had an equal footing in dialogues with municipal authorities.

“We had to start the conversation with ‘how can we help?’ not ‘here’s the solution,’” said Bijvoet.

© The Hague

In Groningen, that approach uncovered deeper issues, such as debt, isolation and legal confusion, and turned energy talks into broader social support.

This local, people-first work added a vital layer to the pilot. It helped translate technical planning into lived experience and ensured that community engagement informed how the broader transition took shape.

© The Hague

The Hague’s journey is a story of persistent innovation and collaborative learning. It shows the raw mechanics of climate transition, from regulatory discussions and financial recalibrations to community dialogue and trust-building. It is, above all, a story of steady progress through collective effort. “There is no silver bullet,” Bijvoet concludes. “But there is a path, and we are on it together.”

Interested in finding out more about the project? Click here