Author: Barbara Jarkiewicz

Stories from Pilot Cities: Stockholm is one of the 112 cities participating in the EU Mission to deliver 100 climate-neutral and smart cities, and the Pilot Cities Programme – a component of the Mission that focuses on exploring and testing pathways to rapid decarbonisation over a two-year period.

When politicians in Stockholm first set their sights on becoming climate positive by 2030, a bolder target than even Sweden’s national 2045 neutrality goal, the city officials knew they could not do it alone. The numbers told a clear story: the city administration could directly fund and deliver only a fifth of the transformation. The rest would depend on businesses, local associations and other city stakeholders.

“It was really clear to us,” said Lisa Enarsson, project manager in the City of Stockholm. “Around 20 per cent of the investments are done by the City, but 80 per cent needs to be done by others who live and work here. The City cannot do this on its own.”

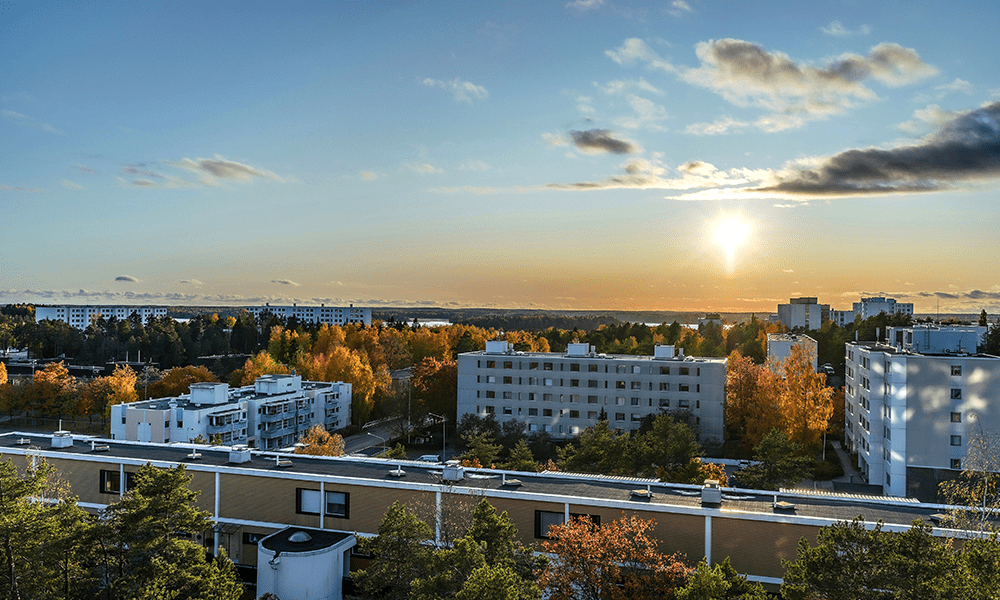

This ambition builds on decades of progress. Stockholm has already reduced its greenhouse gas emissions from 3.4 million tonnes in 1990 to just over 1.1 million tonnes in 2021. Most of these cuts came from decarbonising electricity and heating. But the more challenging task of cutting transport, consumption, and construction emissions now looms ahead, forcing the city to look for new ways to involve its community.

© Stockholm municipality- "Transition arenas" Stakeholders meeting to present and test pilot projects for climate neutrality

That conviction led Stockholm to join the Pilot Cities Programme, where they launched Scale Stockholm, a bold experiment in creating “transition arenas” for climate and health in five city districts.

These arenas bring together civil society, small businesses, and residents not just to brainstorm, but to run their own pilots, 27 so far, testing together how everyday habits, local economies, and urban spaces can be reshaped for a just, inclusive, and healthy climate transition.

A New Kind of Partnership

From the beginning, the process broke with tradition.

“We are not used to working this way. Normally, everything is planned from beginning to end. This time, we said: we don’t know what the outcome will be. We’ll ask the community what transition they want to do, and then support them,” said Enarsson.

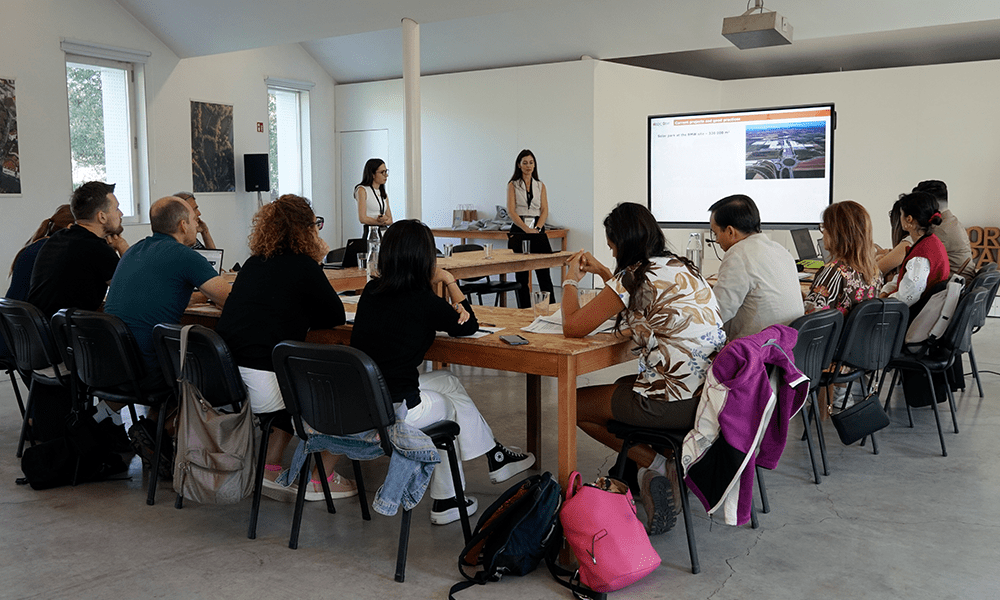

© Stockholm municipality- When civil society and businesses in the local community come together.

For many in the City Administration, that shift was uncomfortable. Adeline Olofsson, the Pilot Cities Programme project manager from the City of Stockholm, recalled:

“It took more time than we expected to get other departments and City districts on board. But the turning point came when we gathered civil society and businesses in the local community together. Suddenly, the room was full of energy. People shared their ideas on energy, mobility, sustainable food, circularity and urban cultivation. They found each other and got stronger by working together co-creating joint actions.”

The approach, described by Olofsson as “bottom-up by design,” has already led to a cultural shift within Stockholm’s administration. Departments once siloed now find themselves collaborating not just with each other but with citizens, associations, and local companies.

“It has really improved our relationships. Now we can connect associations with the right expertise, and that’s a big change,” Olofsson said.

Pilots for the Future

The transition arenas have sparked projects that reflect the diverse needs of Stockholm’s districts. In the Årsta district, housing associations are banding together to form local energy communities, pooling resources to invest in renewables and optimise energy use.

“It’s about resilience,” said Enarsson. “Cutting power peaks, sharing energy, and building local knowledge.”

In central Stockholm, cycling groups have mapped and analysed the Slussen to Djurgården bike corridor, identifying gaps in safety and accessibility for the millions who visit the island’s 60 attractions each year. Their findings were presented to politicians during a cycle ride.

In the Royal Seaport (Norra Djurgårdsstaden), partners are building a zero-food-waste district that aims to cut household waste by 25 per cent through measurement, training, and tenant-led initiatives.

Other pilots focus on circular economies, sustainable food, and community gardening hubs designed to make urban cultivation more inclusive and resilient. Each project is owned not by the City, but by the local associations and companies that conceived them.

“They are the ones driving it. We just provide support by, for example, connecting them with the right department. But ownership stays with them,” explained Olofsson.

© Getty image

Partnerships have been crucial in making this possible. Stockholm has worked closely with Digidem Lab, which brought its experience from running Sweden’s national citizens’ assembly to design inclusive meetings where residents shaped pilot ideas. Training in community organising helped City staff learn new ways of engaging people.

Another partner, SWECO – an architecture agency, is working on a digital map that tracks each pilot and visualises progress, a tool the City now sees as an important deliverable for scaling efforts. As Olofsson noted, “these collaborations really improved our skills on how to work with new methods for dialogue and new ways of engaging civil society.”

Health as a Motivator

A central innovation of Scale Stockholm has been linking climate to health.

“It’s often easier to motivate people when it’s about health,” Enarsson said. “If you start biking, it’s good for your health and it’s good for reducing emissions. Climate and health go hand in hand.”

© Stockholm municipality

This framing has proved especially important in districts with fewer emissions but greater health inequalities.

“Even where CO₂ emissions is not the biggest issue, better living conditions and healthier lifestyles are. And the same measures, better food, less traffic, more active mobility, benefit both,” said Olofsson.

Yet turning that motivation into lasting change also depends on resources. Community projects cannot go so far without financial backing, and here the City has had to experiment with new approaches.

Funding Change Through Collective Effort

The pilots face a familiar challenge: money. While Stockholm provides technical support, it can’t foot the bill.

“We don’t have funding for their actions in the Pilot Cities Programme,” Enarsson explained. “So, we try to find other possibilities, sometimes by writing a letter of intent to strengthen applications or connecting them with the right stakeholders and institutions”.

Here, too, Stockholm looks outward. Inspired by cities like Klagenfurt, Manchester and Paris, it is exploring climate funds and alternative financing mechanisms. Officials have also connected with Bristol to learn about its model.

“There’s a lot of exchange happening. We learn from others, and they learn from us,” said Enarsson.

© Stockholm municipality

Breaking Silos, Changing City Culture

For others, Stockholm’s experiment offers a glimpse into the messy, uncertain, but ultimately rewarding work of systemic transformation.

“The biggest lesson is that it takes time. Time to build trust, to change internal culture, to let go of control. But once people see the benefits, new networks, new energy, new ownership, it’s powerful,” said Olofsson. Enarsson agreed: “This is about breaking silos, not just in the City Administration but between the City and its people. It can’t be ordinary in the old sense. It has to become the new ordinary.”

© Stockholm municipality

The question now is how to scale. Only four of Stockholm’s 11 city districts are part of Scale Stockholm, and officials are already preparing methods to expand the approach. “We have to figure out how to get the others involved,” Enarsson said, describing plans to embed co-creation processes in the next City budget and make them part of everyday administration.

The challenge is cultural as much as technical, marrying environmental colleagues with those working on social sustainability, and breaking down silos between transport, waste management, and health. The goal is to transition from an innovative pilot to embedding these activities as part of ordinary work without losing the bottom-up spirit that made it successful.

With its 27 pilots underway, a digital map to track their progress, and a growing coalition of residents, associations, and officials, Stockholm is betting that the bottom-up model can scale citywide and beyond.